Evolution of LLMs

The landscape of language models(LMs) has evolved dramatically since the introduction of the Transformer architecture in 2017. Here we will explore the

- mathematical foundations

- architectural innovations

- training breakthroughs

We will talk about everything the code, math, and ideas that revolutionized NLP.

Additionally you can treat this blog as a sort of part 2, to my original blog on transformers which you can checkout here.

How this blog is structured

We will go year by year, going through the revolutionary ideas introduced by each paper.

In the beginning of each section, I have added the abstract, as well as the authors. I have done this to show you, the people were involved behind each idea. As well as what they felt like was the main contribution of their paper.

Below that I have provided the link to the original paper as well as my own implementation of it, subsequently there is a quick summary section which you can skim over if you feel like you know the crux behind the idea.

Note: All the quick summaries are AI generated, and may contain some mistakes. The core content is all human generated though, so it definitely contains mistakes :)

After that, each section contains intuition, code, and mathematical explanation (wherever required) for each idea. I have tried to add all the prerequisite knowledge wherever possible (Like the PPO section contains derivation of policy gradient methods, as well as explanation for TRPO). I have provided links to resources wherever I have felt I cannot provide enough background or do sufficient justice to the source material.

Additionally there has been a lot of innovation in vision modeling, TTS, Image gen, Video gen etc each of which deserves it’s own blog(And there will be!! I promise you that). As this is primarily an LLM blog, I will just give quick intro and links to some ground breaking innovations involving other ML papers.

Note: Do not take for granted all the hardware, data and benchmark innovations. Though I will briefly mention them. I implore you to explore them further if they interest you. This blog is strictly restricted to breakthroughs in Large Language Models, and mostly open source one’s. Even though current models by OpenAI, Anthropic, Google etc are amazing, not much is known about them to the public. So we will only briefly talk about them.

The AI timeline

This is a timeline of the most influential work. To read about more architectures that were huge at the time but died down eventually, consider going through the Transformer catalog.

The blog “Transformer models: an introduction and catalog — 2023 Edition” helped me immensely while making the timeline. Additionally this blog was helpful too.

| Links post 2019 are broken as it’s still work in progress |

2017

2018

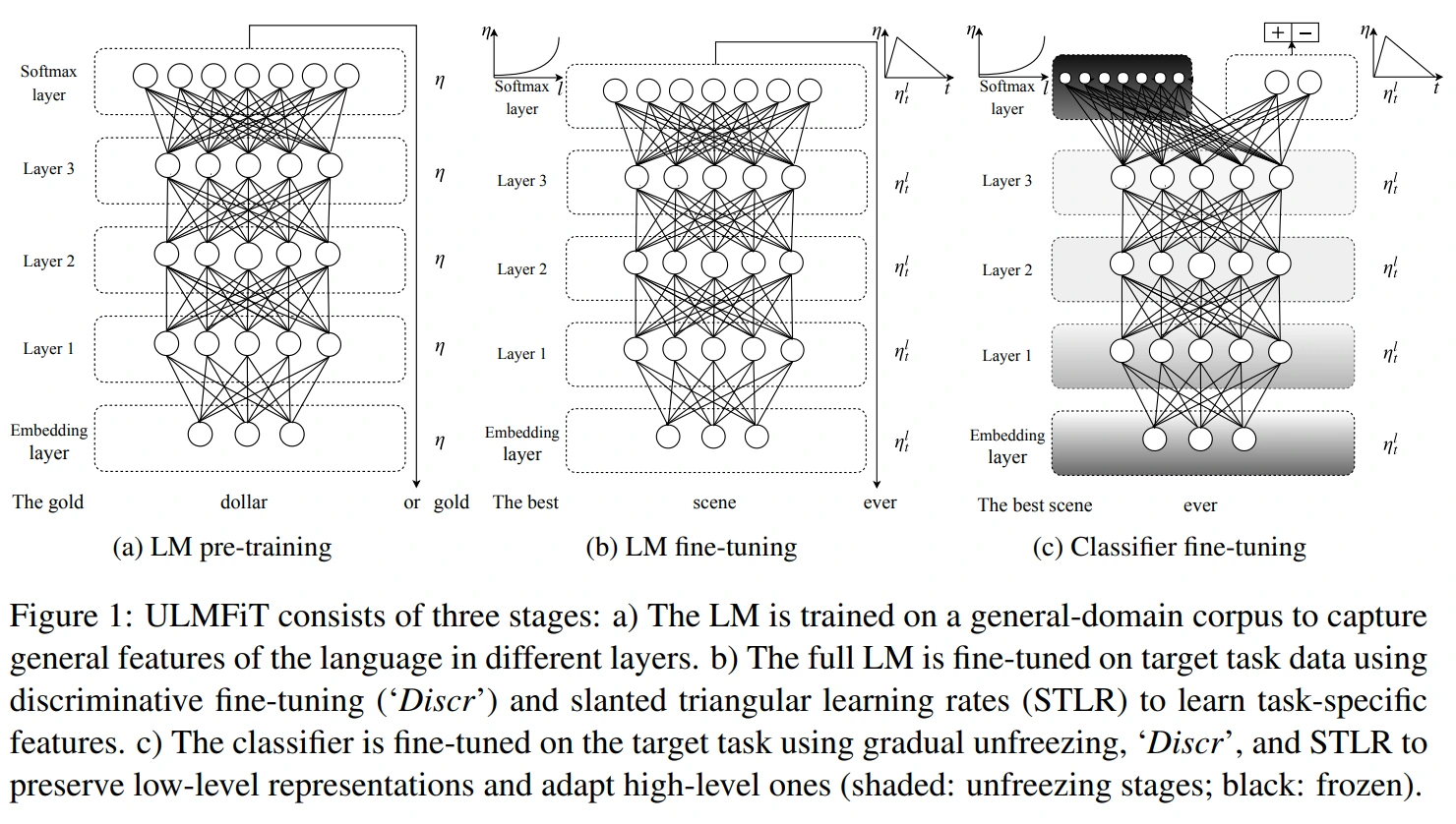

- Universal Language Model Fine-tuning for Text Classification

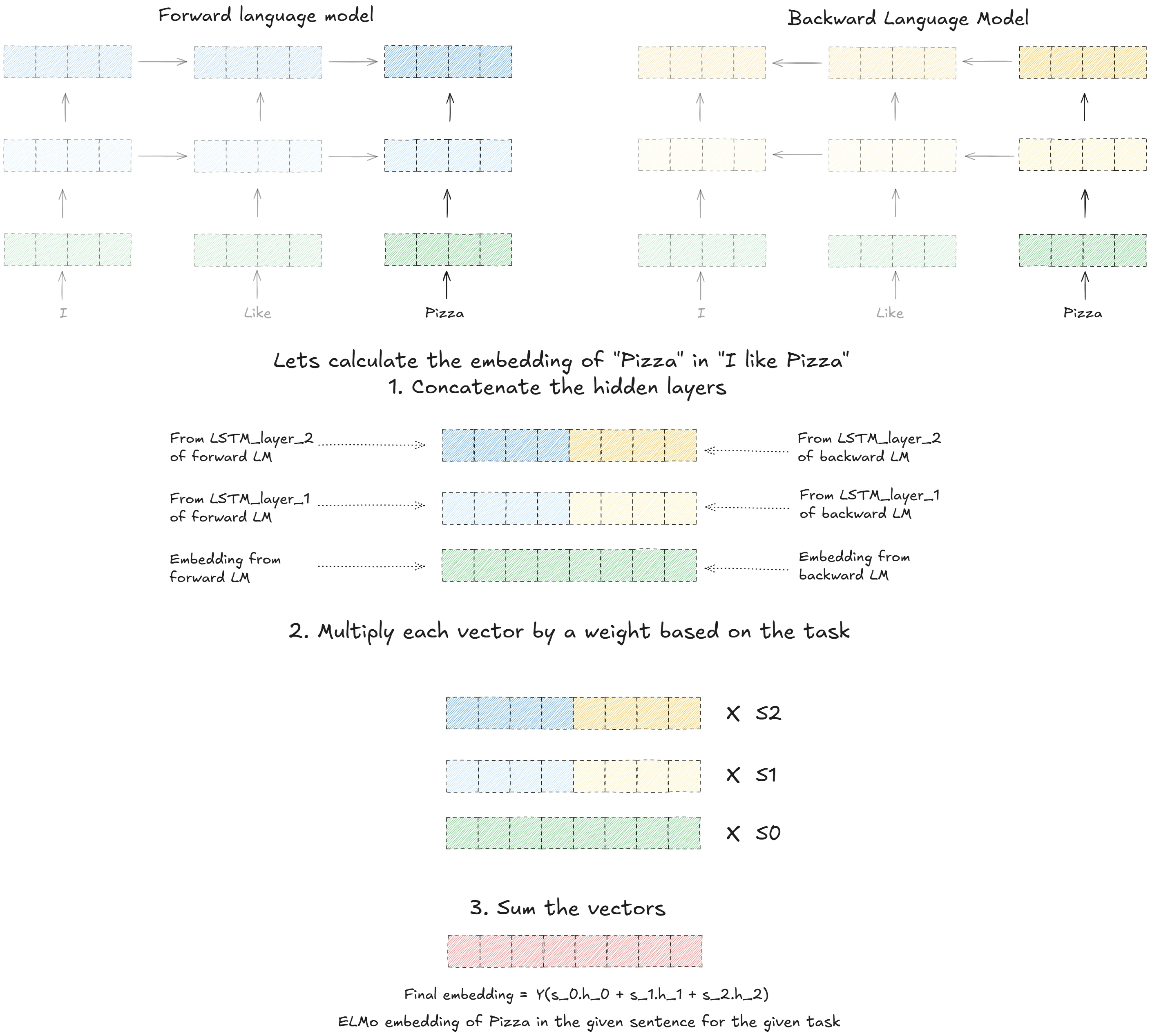

- Deep contextualized word representations

- Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-Training

- SentencePiece: A simple and language independent subword tokenizer and detokenizer for Neural Text Processing

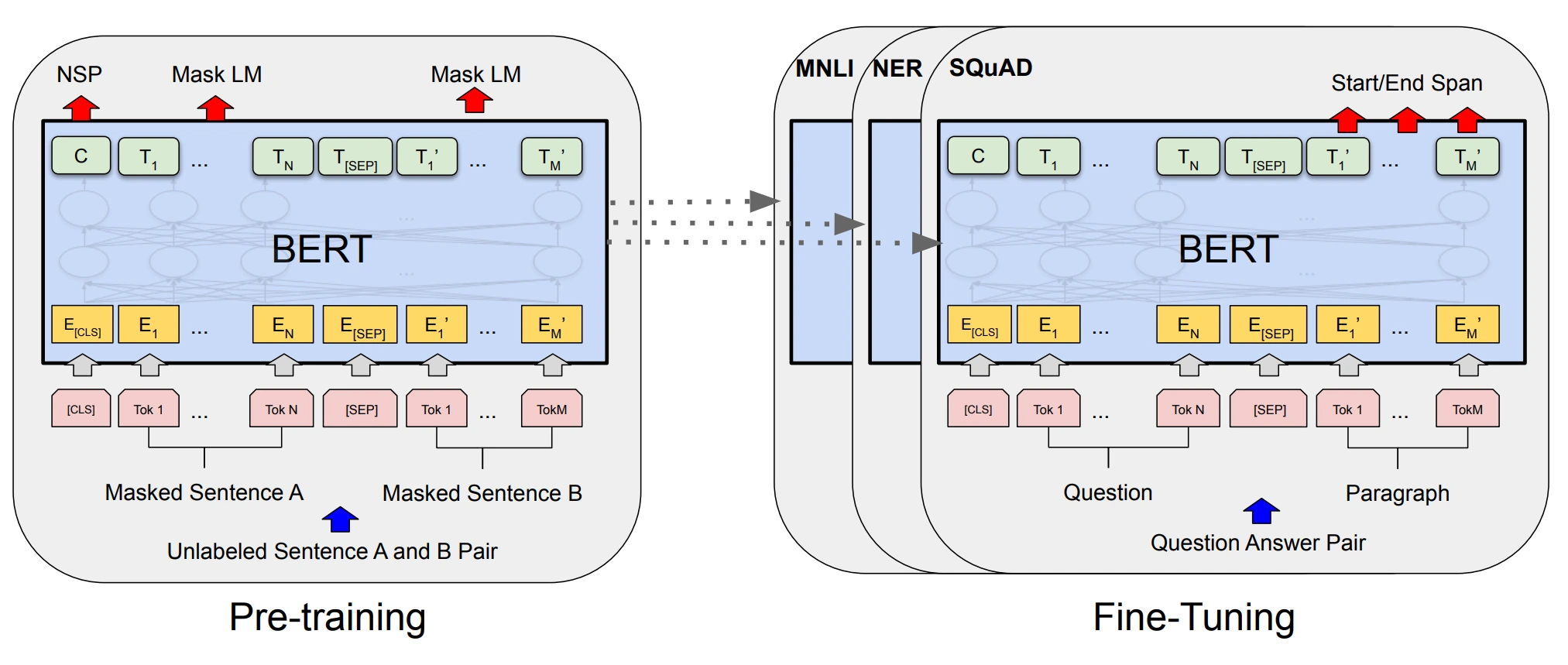

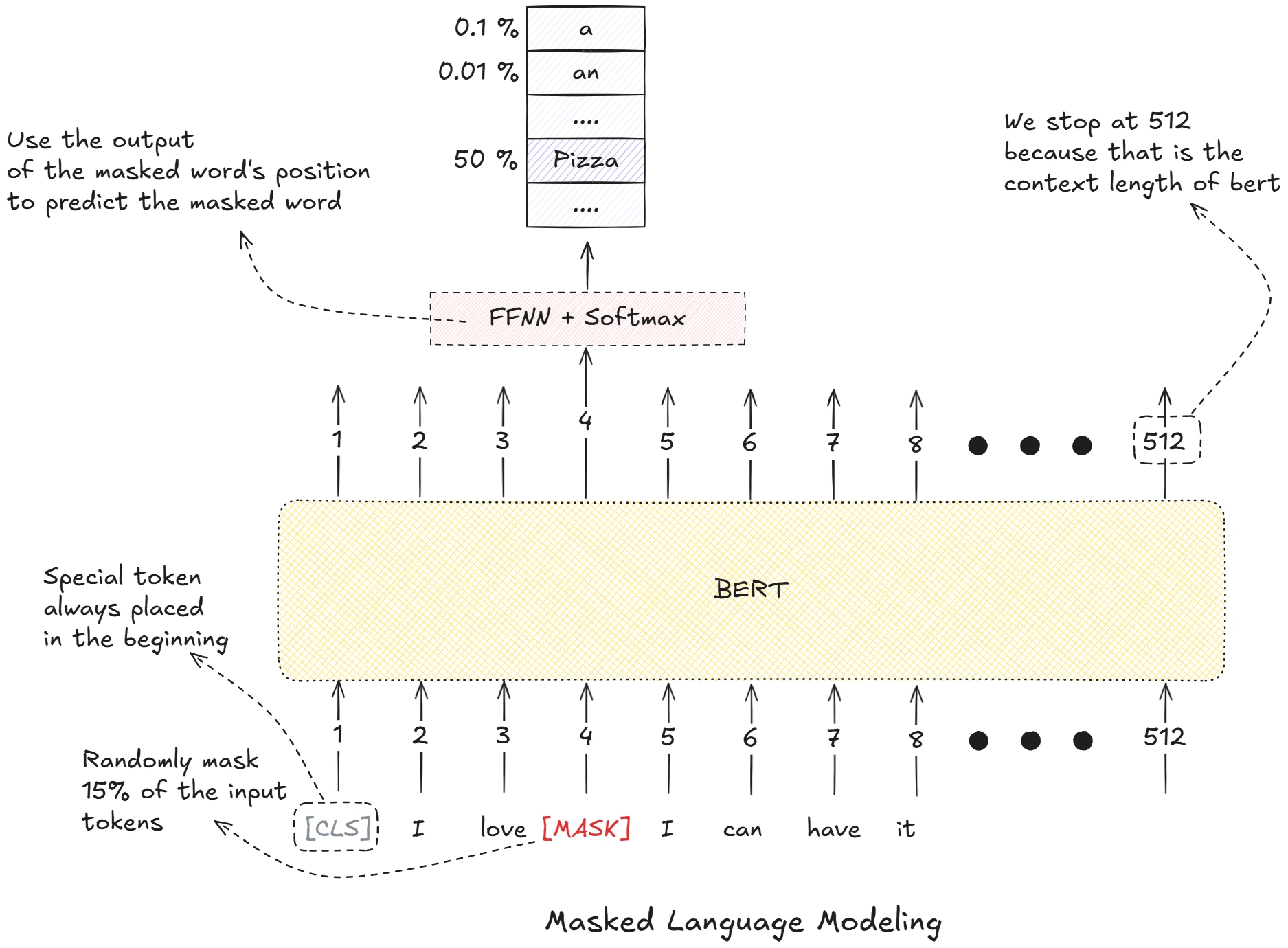

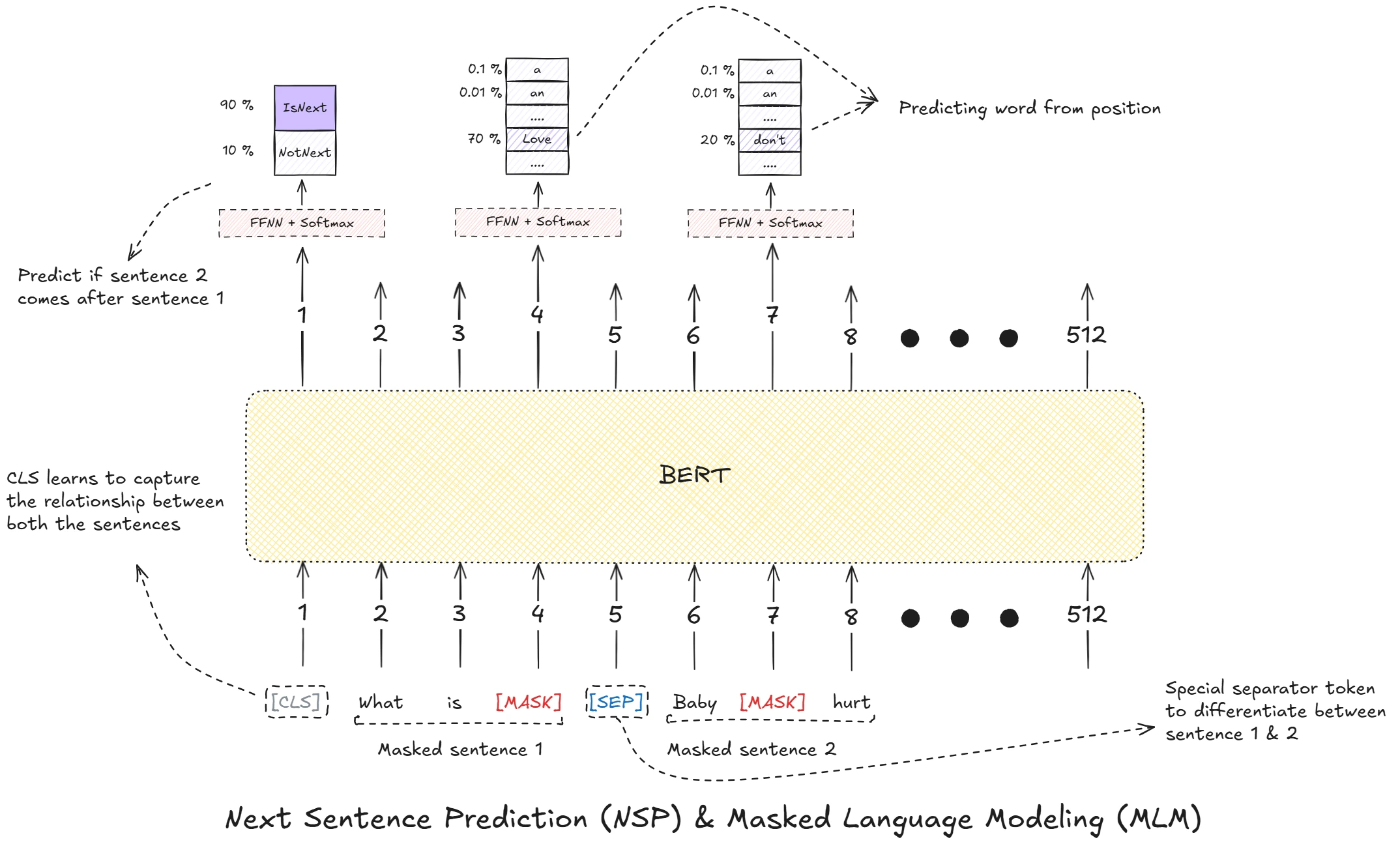

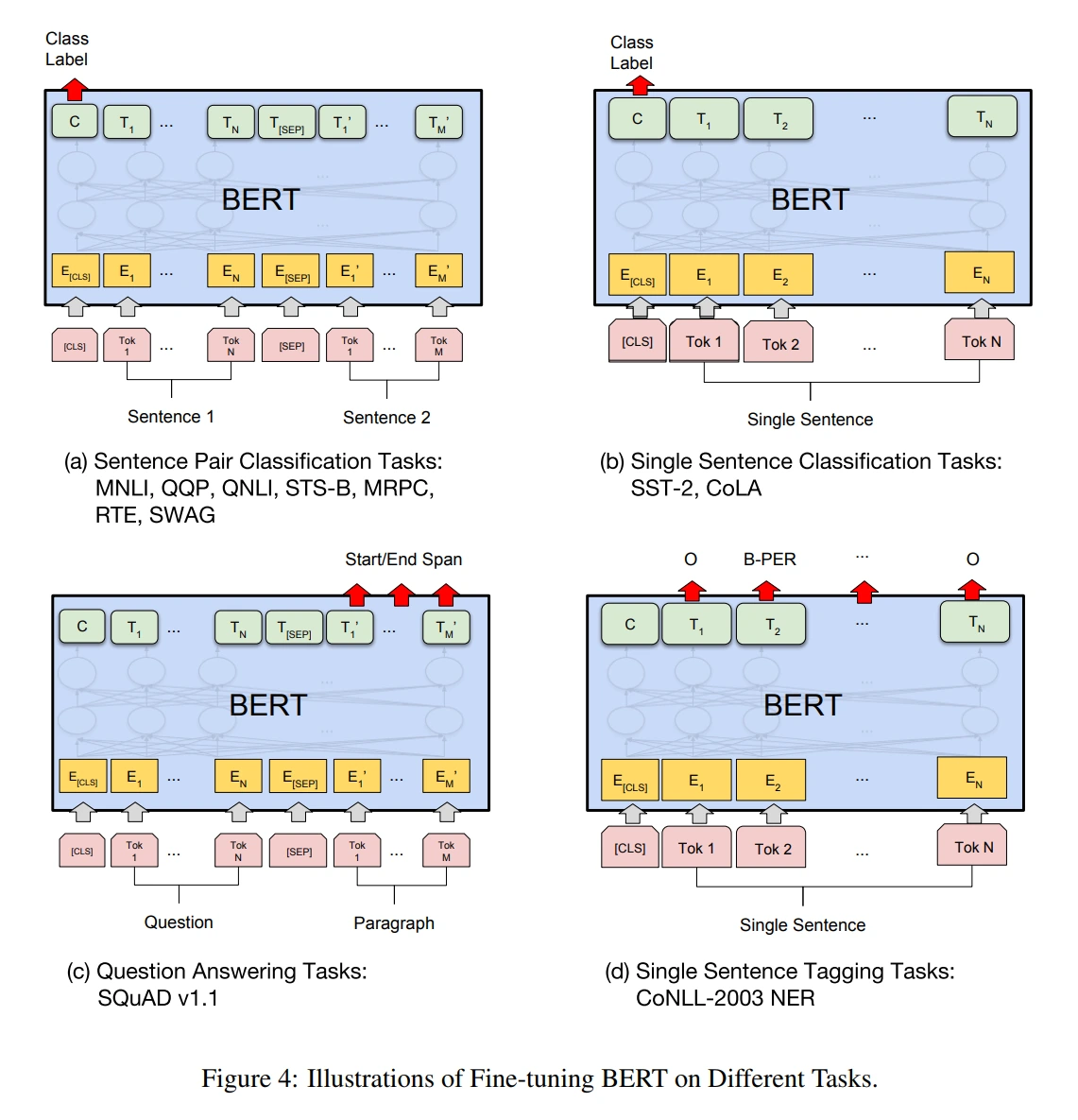

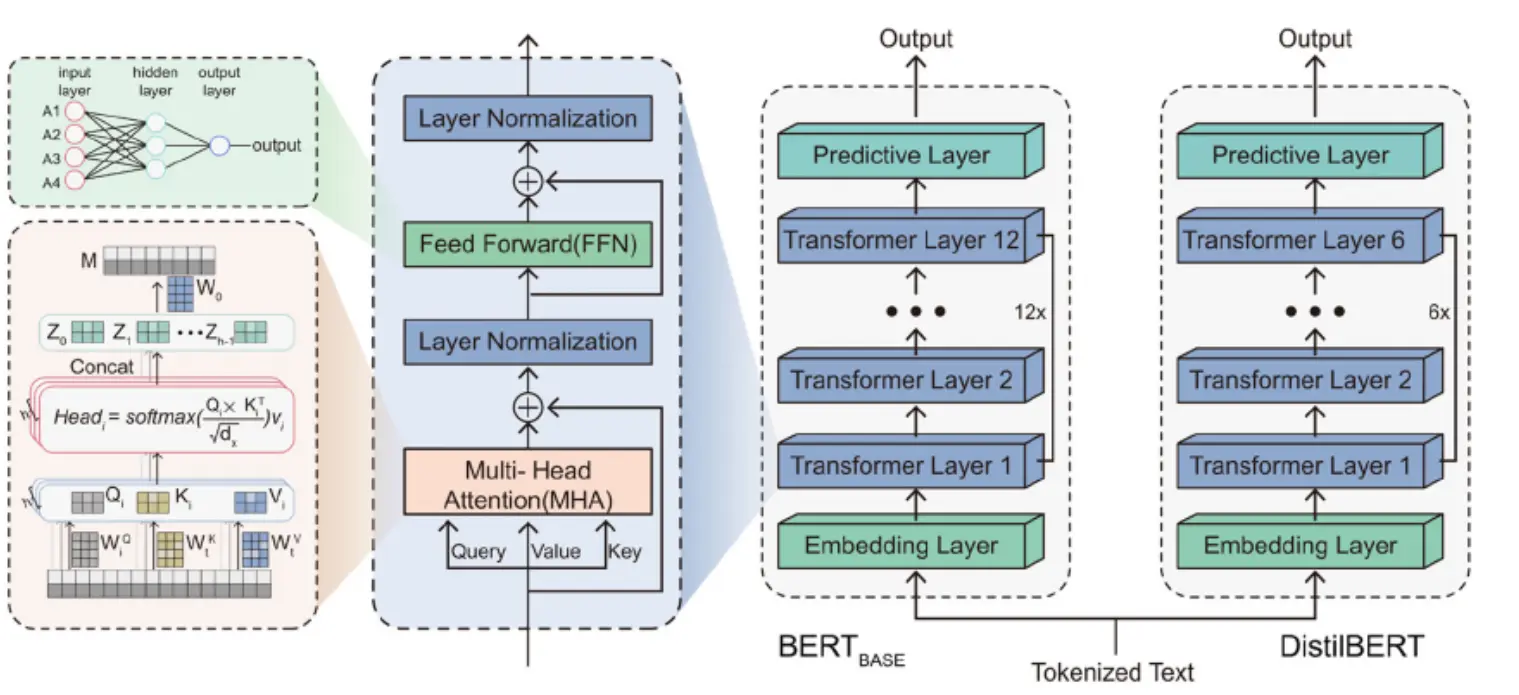

- BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding

2019

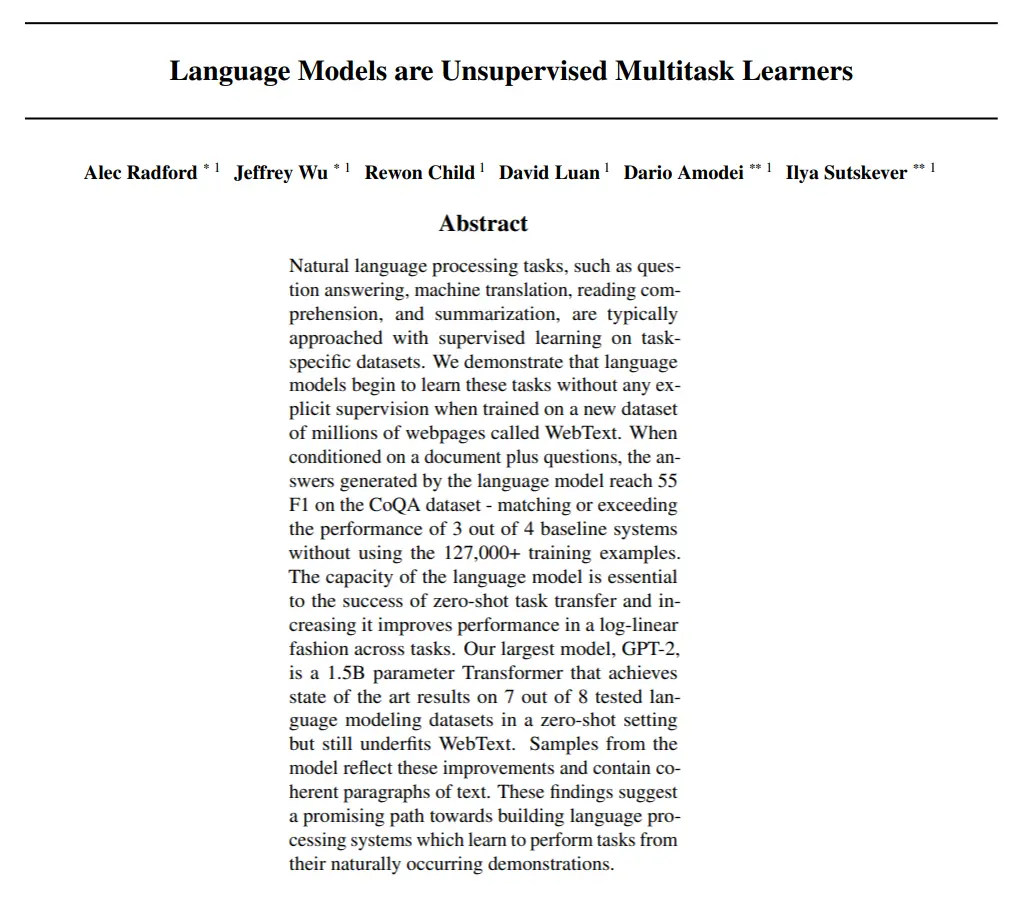

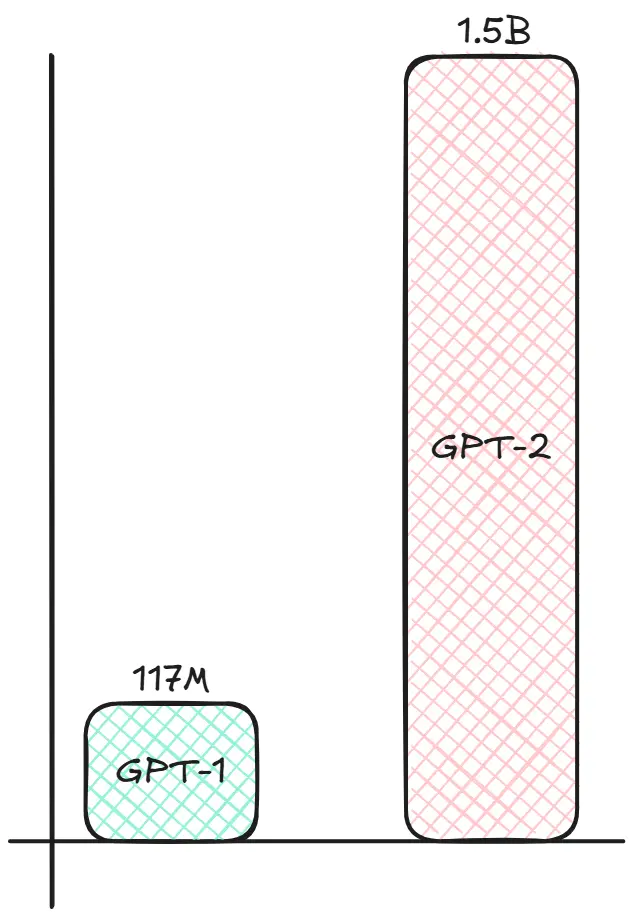

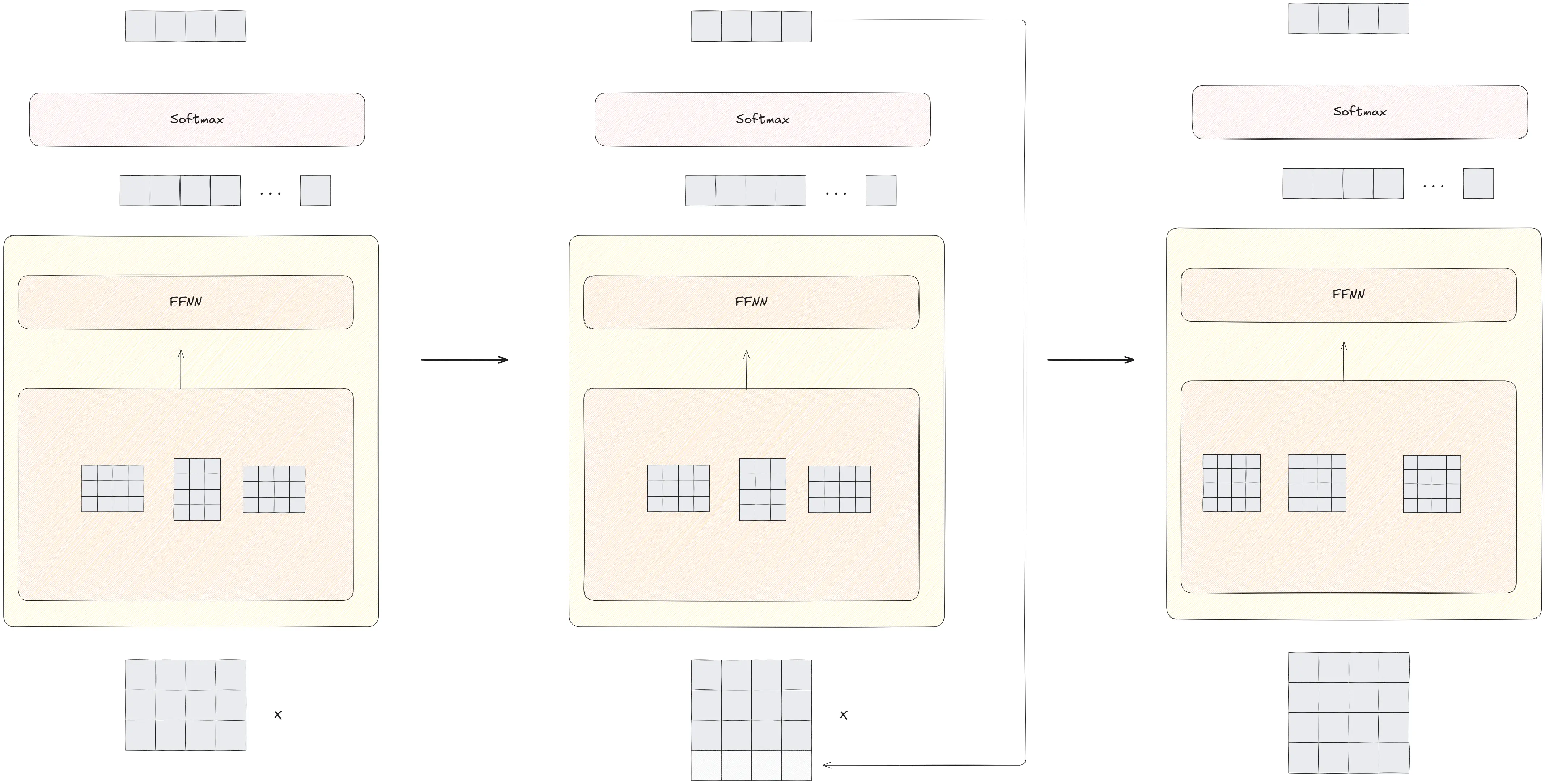

- Language Models are Unsupervised Multitask Learners

- RoBERTa: A Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach

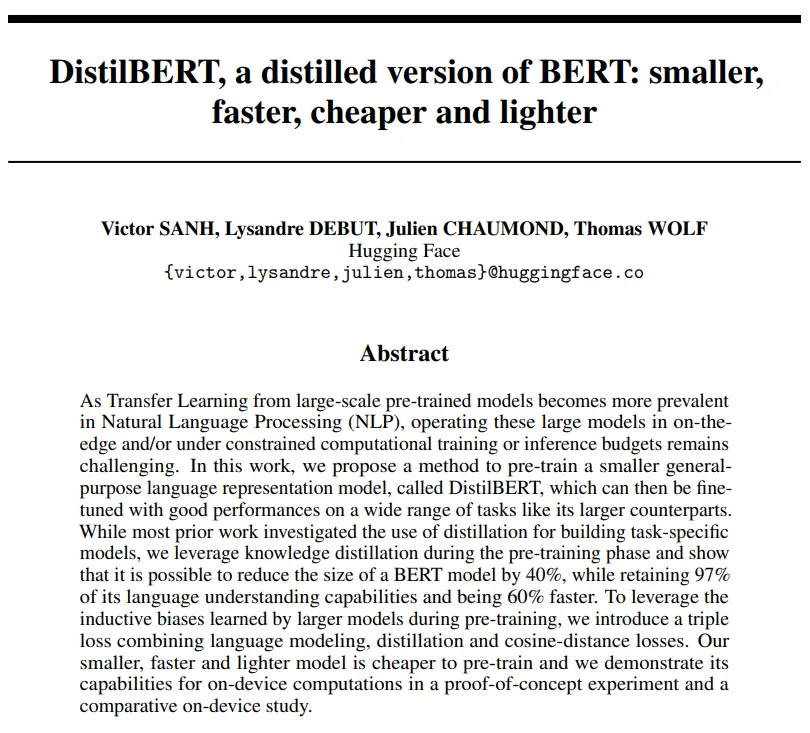

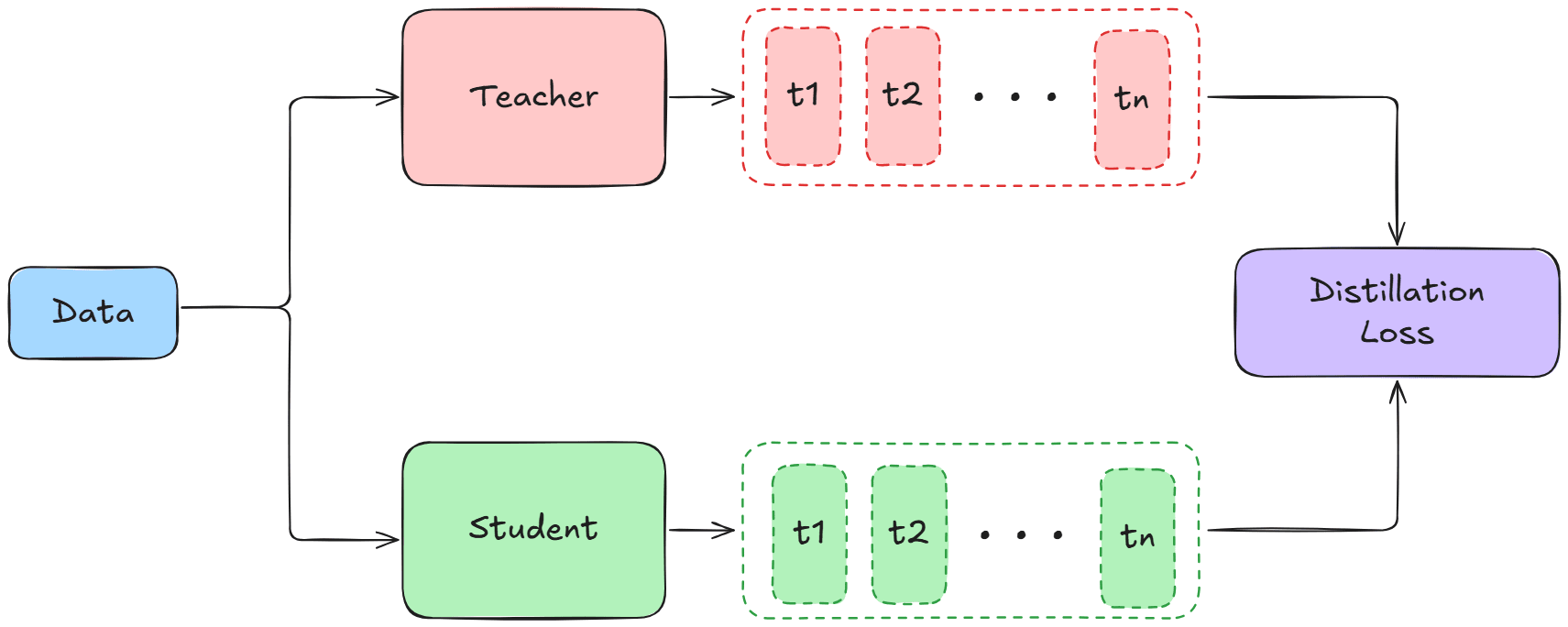

- DistilBERT, a distilled version of BERT: smaller,faster, cheaper and lighter

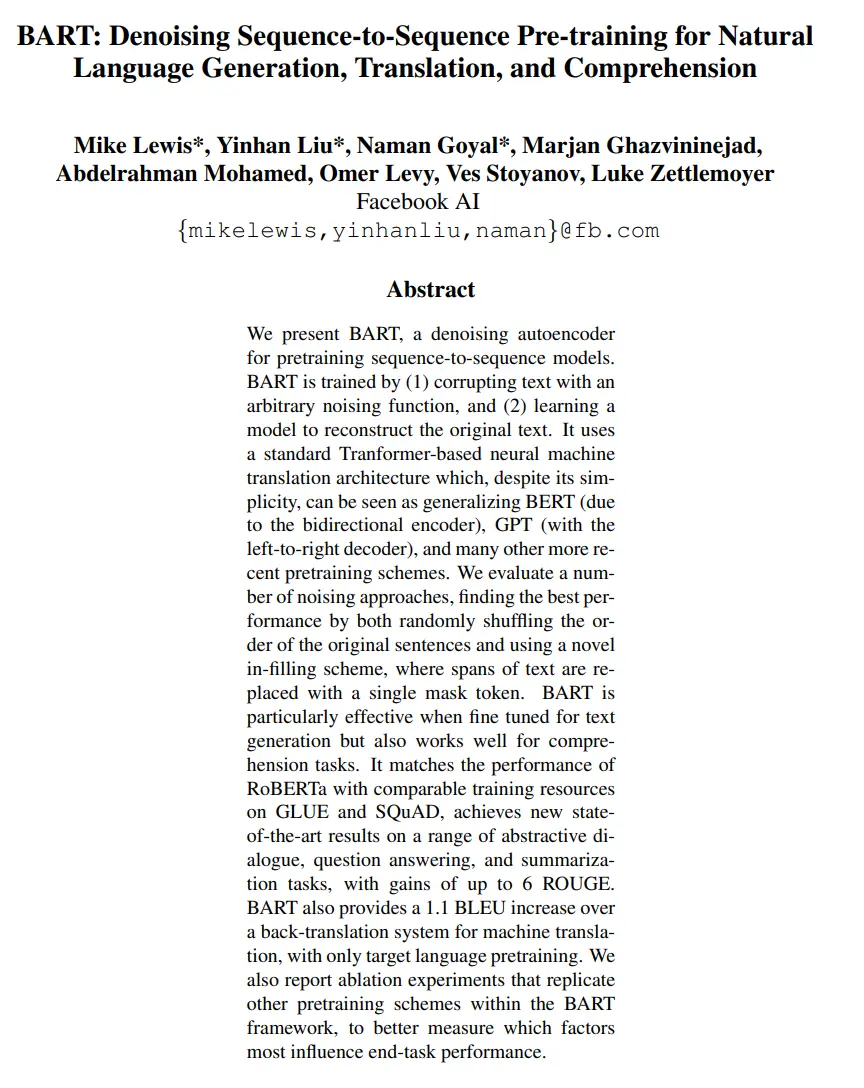

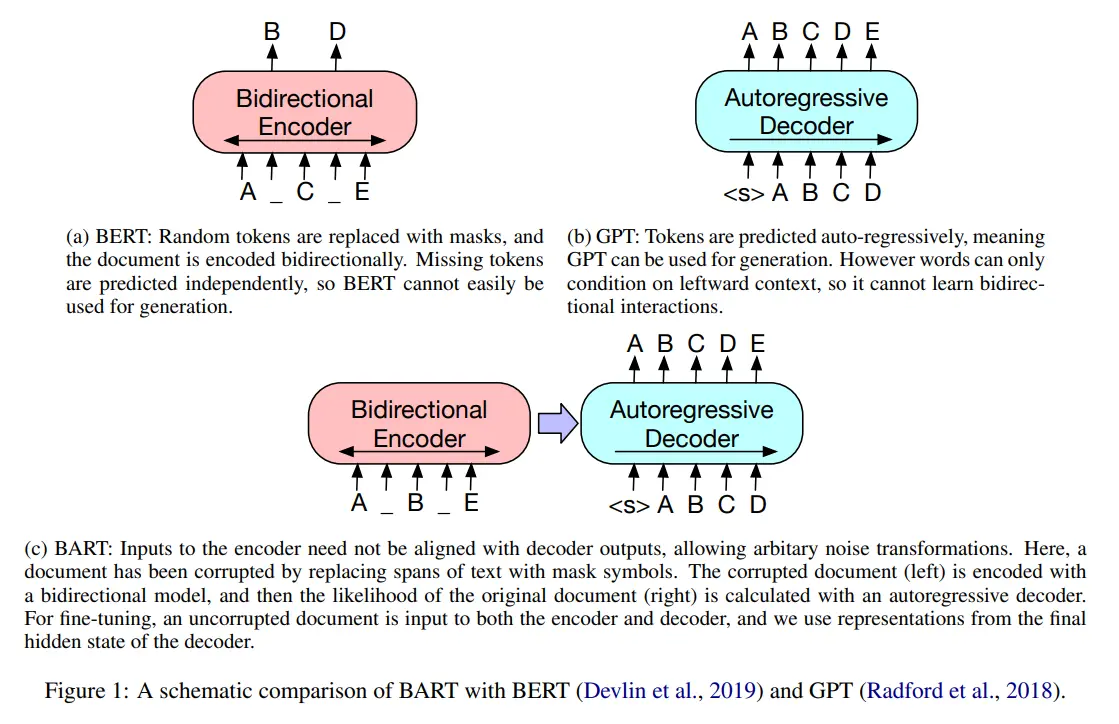

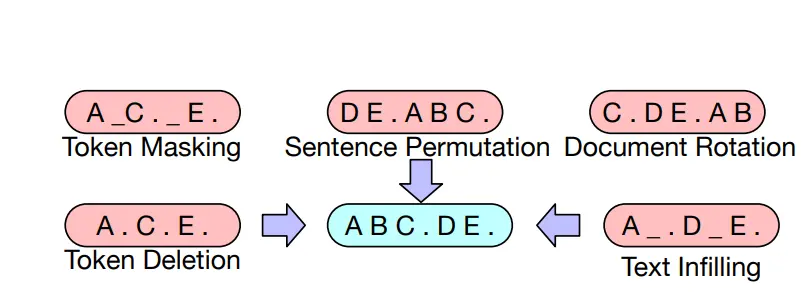

- BART: Denoising Sequence-to-Sequence Pre-training for Natural Language Generation, Translation, and Comprehension

- XLNet: Generalized Autoregressive Pretraining for Language Understanding

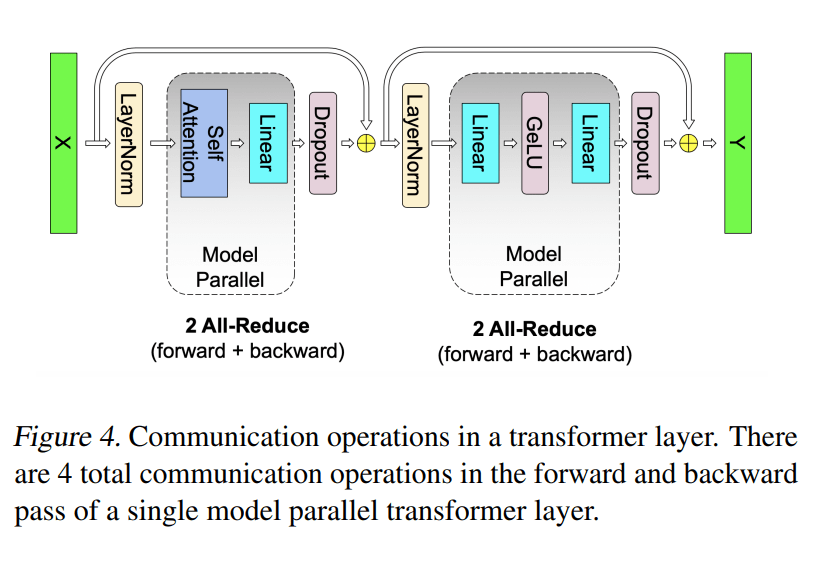

- Megatron-LM: Training Multi-Billion Parameter Language Models Using Model Parallelism

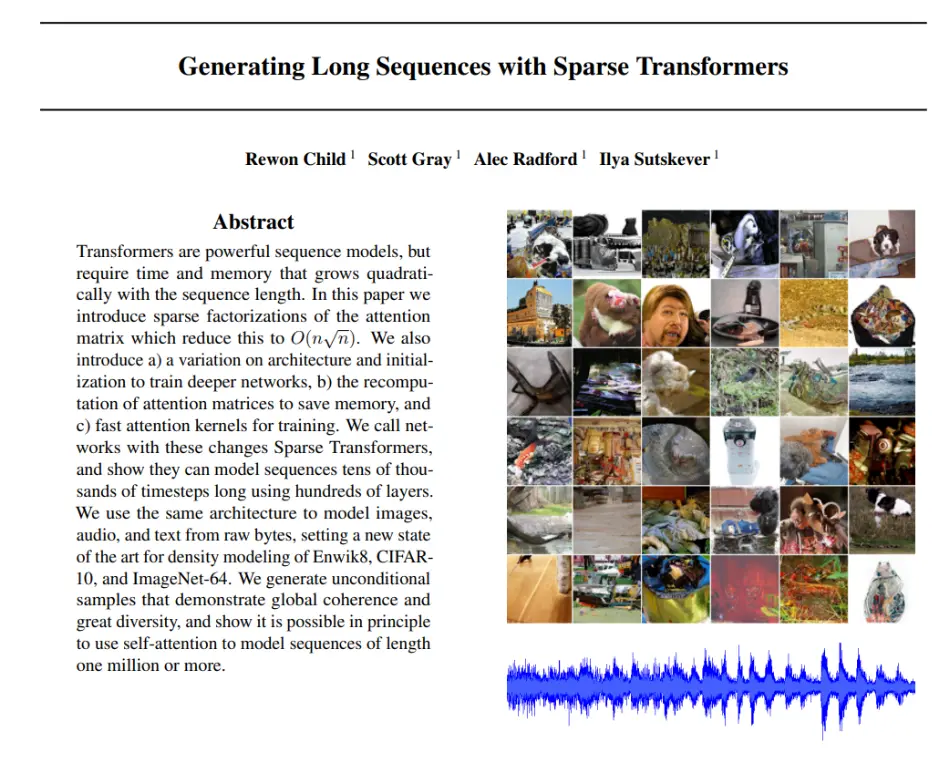

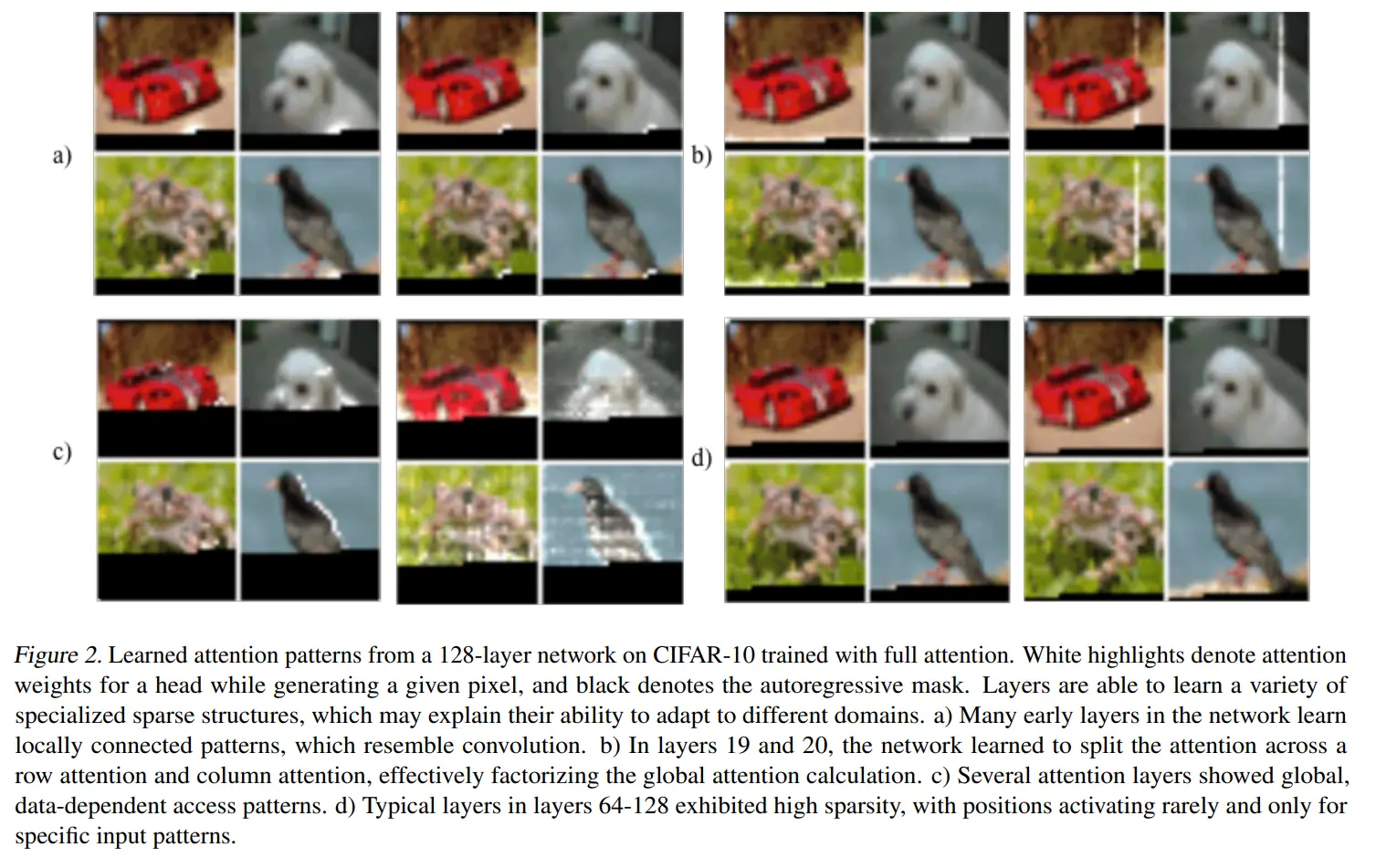

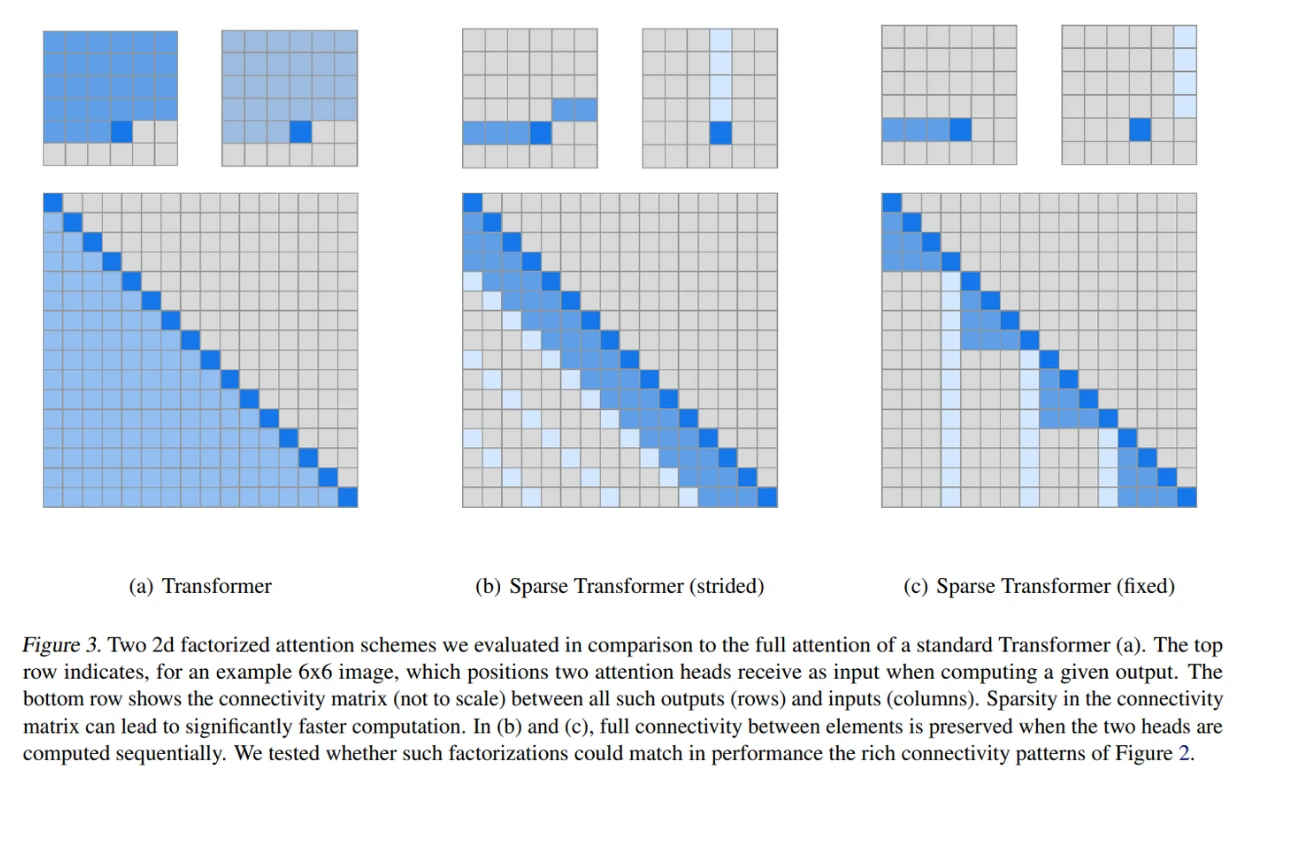

- Generating Long Sequences with Sparse Transformers

2020

- Reformer: The Efficient Transformer

- Longformer: The Long-Document Transformer

- GShard: Scaling Giant Models with Conditional Computation and Automatic Sharding

- Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks

- Big Bird: Transformers for Longer Sequences

- GPT-3

- Rethinking Attention with Performers

- T5

- Measuring Massive Multitask Language Understanding

- ZeRO (Zero Redundancy Optimizer)

- ELECTRA

- Switch Transformer

- Scaling Laws

2021

- RoFormer: Enhanced Transformer with Rotary Position Embedding

- Efficient Large-Scale Language Model Training on GPU Clusters Using Megatron-LM

- Transcending Scaling Laws with 0.1% Extra Compute

- Improving language models by retrieving from trillions of tokens

- CLIP

- Dall-e

- FSDP

- HumanEval

- LoRA

- Self-Instruct: Aligning Language Models with Self-Generated Instructions

- PaLM

- Gopher (DeepMind)

- Megatron-Turing NLG

2022

- EFFICIENTLY SCALING TRANSFORMER INFERENCE

- Fast Inference from Transformers via Speculative Decoding

- Chinchilla

- Chain-of-thought prompting

- InstructGPT

- BLOOM

- Emergent Abilities of Large Language Models

- Flash Attention

- Grouped-query attention

- ALiBi position encoding

- DeepSpeed Inference: Enabling Efficient Inference of Transformer Models at Unprecedented Scale

- Claude 1

- FLAN (Fine-tuned LAnguage Net) (Google)

- Red Teaming Language Models with Language Models

- HELM (Holistic Evaluation of Language Models)

- DALL-E 2 (OpenAI)

- Stable Diffusion (Stability AI)

- GPTQ

- Beyond the Imitation Game: Quantifying and extrapolating the capabilities of language models

- Minerva

- ChatGPT

2023

- Efficient Memory Management for Large Language Model Serving with PagedAttention

- QLoRA: Efficient Finetuning of Quantized LLMs

- Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning Methods for Pretrained Language Models: A Critical Review and Assessment

- FlashAttention-2: Faster Attention with Better Parallelism and Work Partitioning

- AWQ: Activation-aware Weight Quantization for LLM Compression and Acceleration

- Generative Agents: Interactive Simulacra of Human Behavior

- Voyager: An Open-Ended Embodied Agent with Large Language Models

- Universal and Transferable Adversarial Attacks on Aligned Language Models

- Tree of Thoughts: Deliberate Problem Solving with Large Language Models

- Mpt

- WizardLM: Empowering Large Language Models to Follow Complex Instructions

- DeepSpeed-Chat: Easy, Fast and Affordable RLHF Training of ChatGPT-like Models at All Scales

- GPT-4

- Mistral 7b

- LLaMA

- Mixtral 8x7B

- LLaMA 2

- Vicuna (LMSYS)

- Alpaca

- Direct Preference Optimization (DPO)

- Constitutional AI

- Toy Models of Superposition

- Towards Monosemanticity: Decomposing Language Models With Dictionary Learning

- PaLM 2

- LAION-5B (LAION)

- LIMA

- Mamba

- LLaVA (Visual Instruction Tuning)

- Claude 1/Claude 2

- Gemini

- Qwen

- Qwen-VL

- Phi-1

- Reinforced Self-Training (ReST) for Language Modeling

- The Era of 1-bit LLMs: All Large Language Models are in 1.58 Bits

2024

- Gemma

- Gemma 2

- Chatbot Arena: An Open Platform for Evaluating LLMs by Human Preference

- TinyLlama: An Open-Source Small Language Model

- MordernBert

- Jamba: A Hybrid Transformer-Mamba Language Model

- Claude 3

- LLaMA 3

- Gemini 1.5

- Qwen 2

- phi-2/phi-3

- OpenAI o1

- RSO (Reinforced Self-training with Online feedback)

- SPIN (Self-Played Improvement Narration)

- DBRX

- FlashAttention-3: Fast and Accurate Attention with Asynchrony and Low-precision

- Qwen 2.5 (Alibaba)

- DeepSeek 2.5 (DeepSeek)

- Claude 3.5 Sonnet (Anthropic)

- DeepSeek-R1 (DeepSeek)

- Phi 3

- Phi 4

- Self-Play Fine-Tuning Converts Weak Language Models to Strong Language Models

2025

Note: I am releasing this blog early as a preview to get feedback from the community. It is still a work in progress and I plan to explain as well as implement each paper from each year. Do let me know your thoughts through my socials, or in the comments below!!!

2017: The Foundation Year

Transformer

Link to paper: Attention is all you need

Link to implementation: [WORK IN PROGRESS]

Quick Summary

This is the famous “Attention Is All You Need” paper by Vaswani et al. that introduced the Transformer architecture - a groundbreaking neural network model that revolutionized natural language processing.

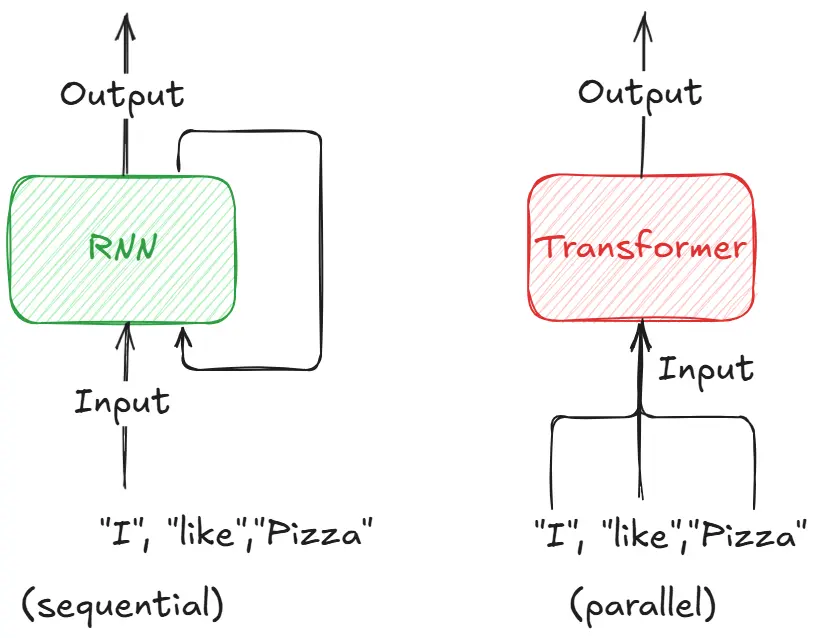

Key Innovation

The paper proposes replacing traditional recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and convolutional networks with a model based entirely on attention mechanisms. The core insight is that self-attention can capture dependencies between words regardless of their distance in a sequence, without needing to process them sequentially.

Architecture Highlights

- Encoder-Decoder Structure: 6 layers each, with multi-head self-attention and feed-forward networks

- Multi-Head Attention: Uses 8 parallel attention heads to capture different types of relationships

- Positional Encoding: Sine/cosine functions to inject sequence order information

- No Recurrence: Enables much better parallelization during training

Results The Transformer achieved state-of-the-art performance on machine translation tasks:

- 28.4 BLEU on English-to-German (WMT 2014)

- 41.8 BLEU on English-to-French

- Trained significantly faster than previous models (12 hours vs. days/weeks)

Impact This architecture became the foundation for modern language models like BERT, GPT, and others. The paper’s core principle - that attention mechanisms alone are sufficient for high-quality sequence modeling - fundamentally changed how we approach NLP tasks.

The work demonstrated superior performance while being more parallelizable and interpretable than previous sequence-to-sequence models.

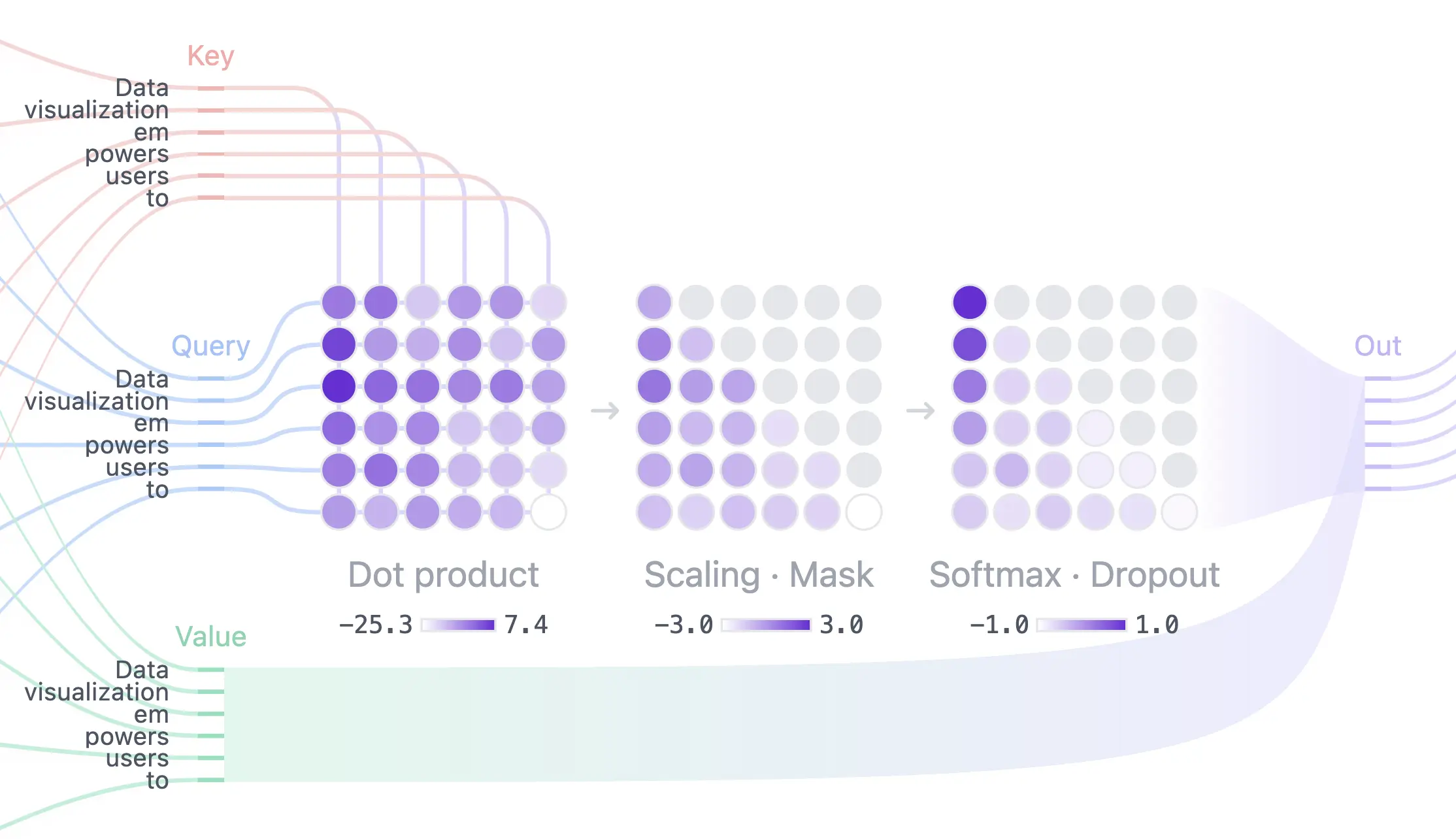

THE foundational paper that introduced some key ideas such as:

- Scaled dot-product attention

- Multi-head attention mechanism

- Positional encodings

- Layer normalization

- Masked attention for autoregressive models

We have talked deeply about each of these topics previously and I implore you to check that part out here.

Problem

Sequential models like RNNs and LSTMs process text word-by-word, creating a fundamental bottleneck: each word must wait for the previous word to be processed. This sequential nature makes training painfully slow and prevents the model from understanding long-range dependencies effectively.

For example, in the sentence “The cat that lived in the house with the red door was hungry”, by the time the model reaches “was hungry”, it has largely forgotten about “The cat” due to the vanishing gradient problem. The model struggles to connect distant but related words.

Solution

The Transformer replaced sequential processing with parallel attention mechanisms. Instead of processing words one-by-one, it looks at all words simultaneously and uses attention to determine which words are most relevant to each other, regardless of their distance in the sentence.

This attention-based approach allows the model to directly connect “The cat” with “was hungry” in a single step, while also enabling massive parallelization during training - turning what used to take weeks into hours.

Training a Transformer

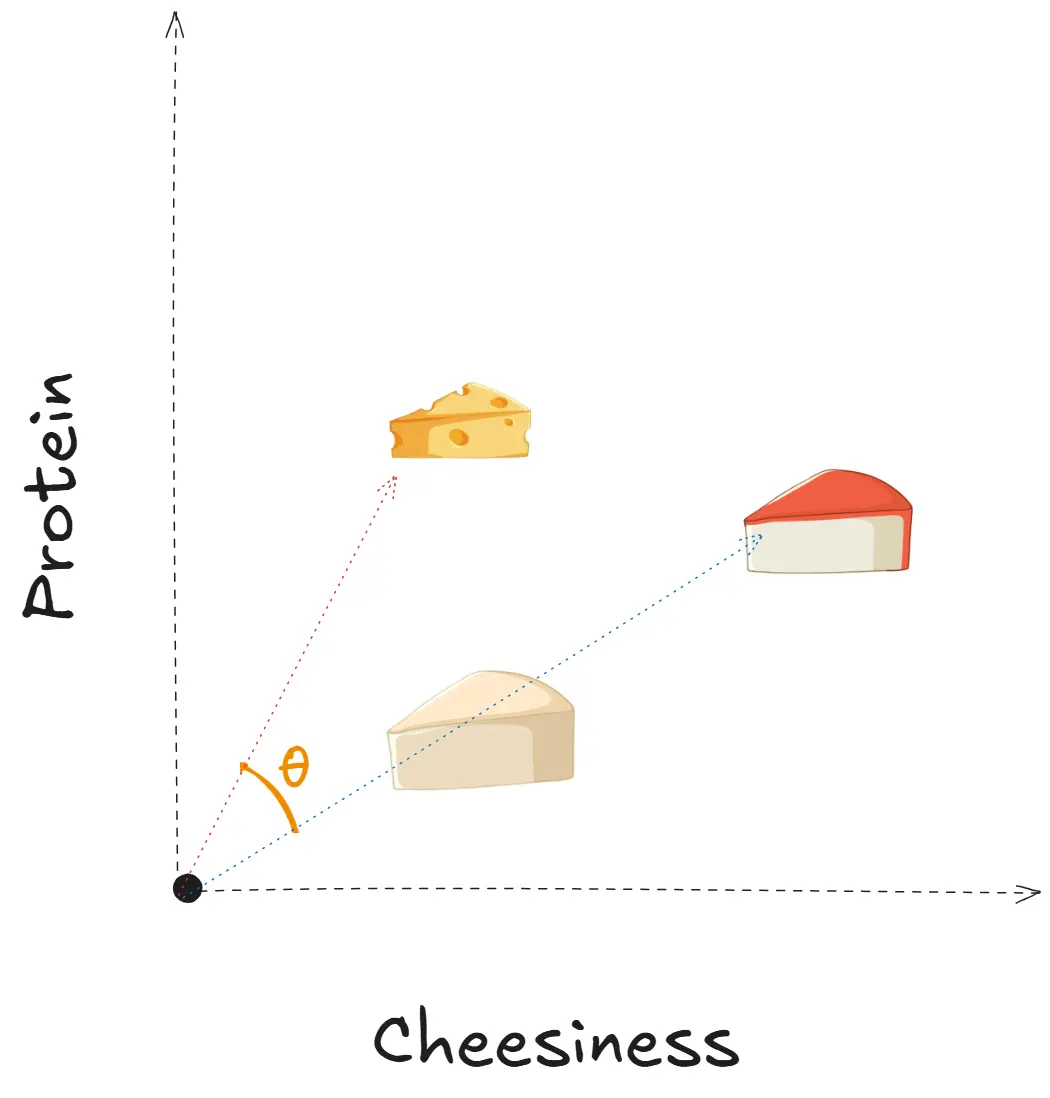

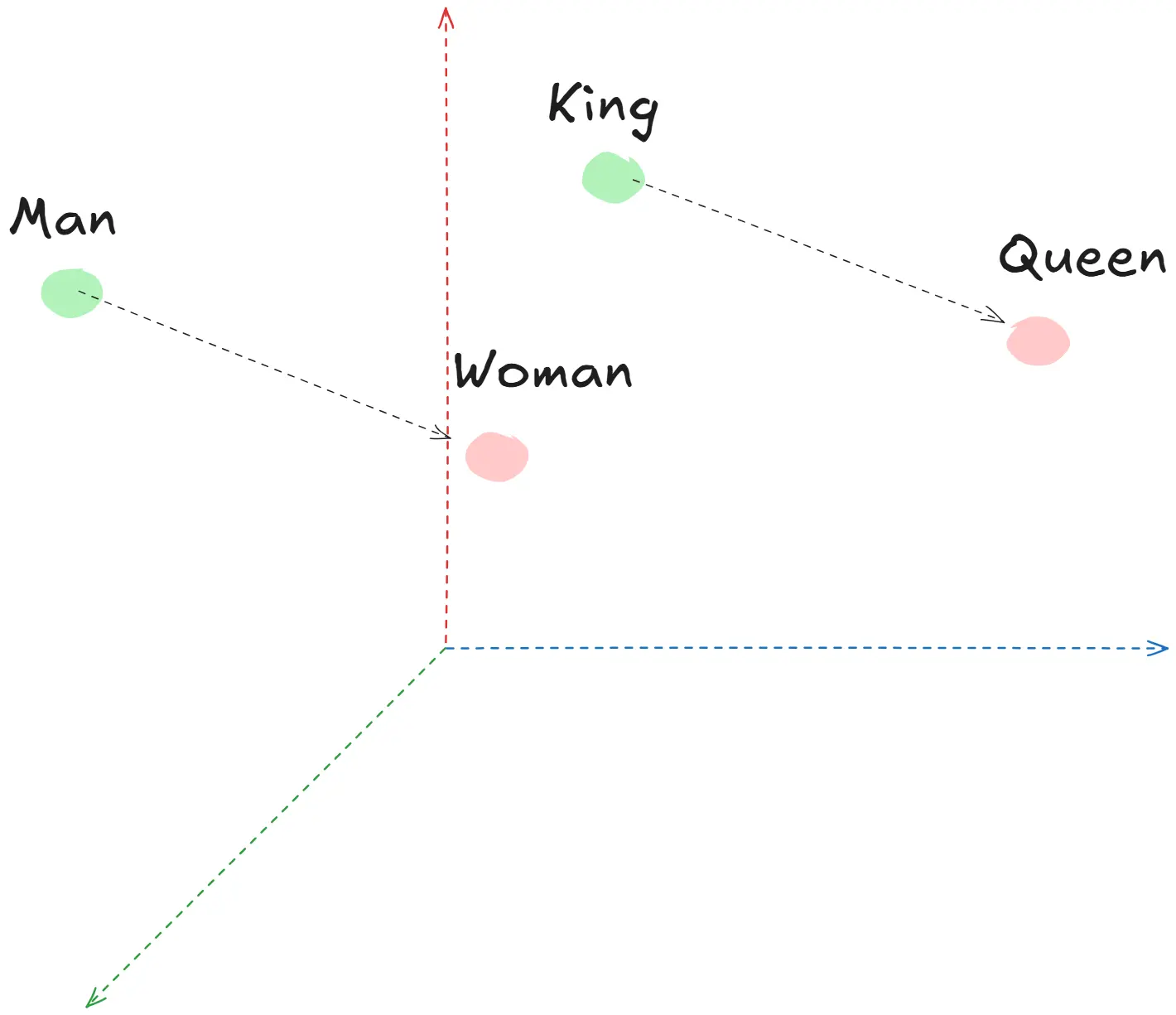

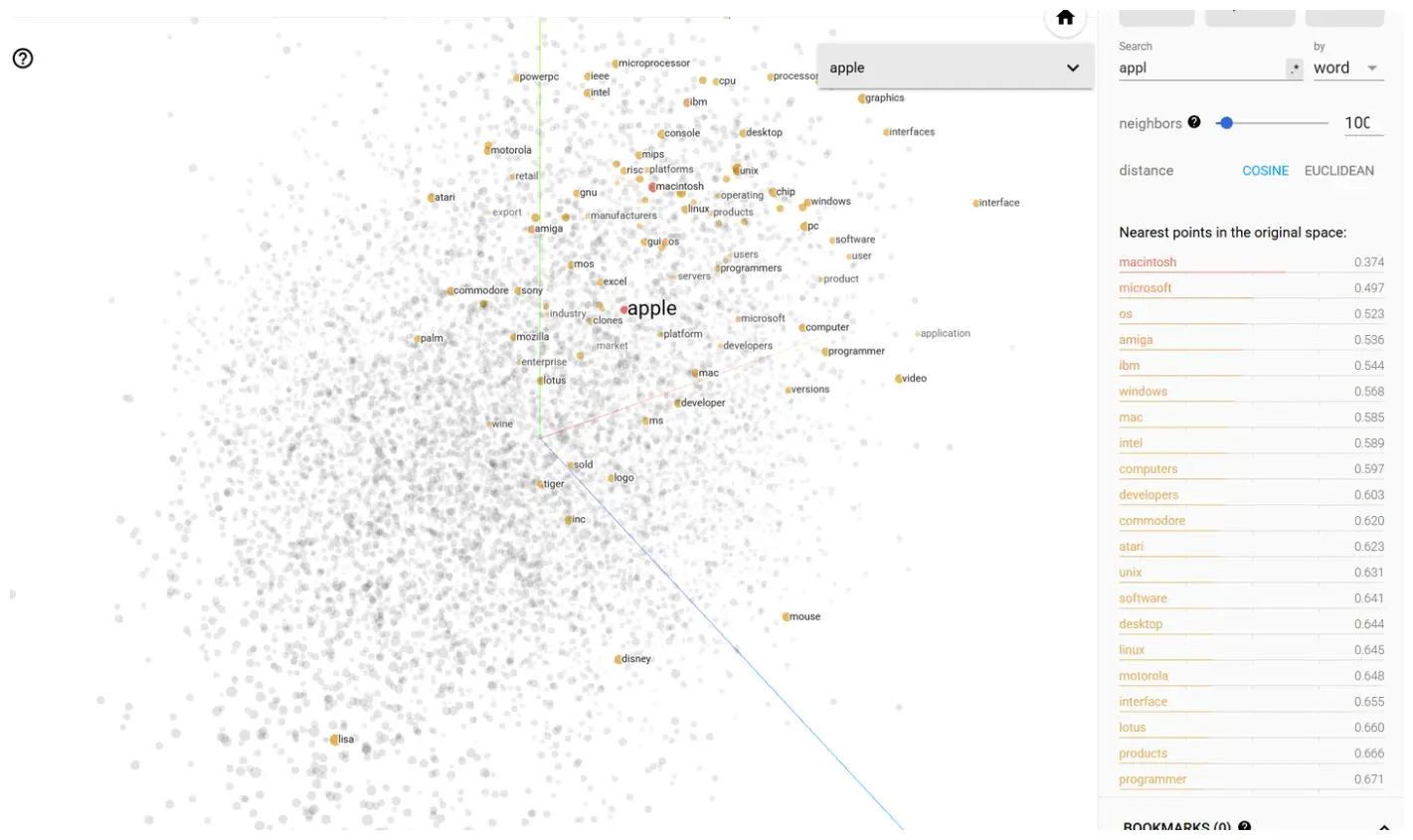

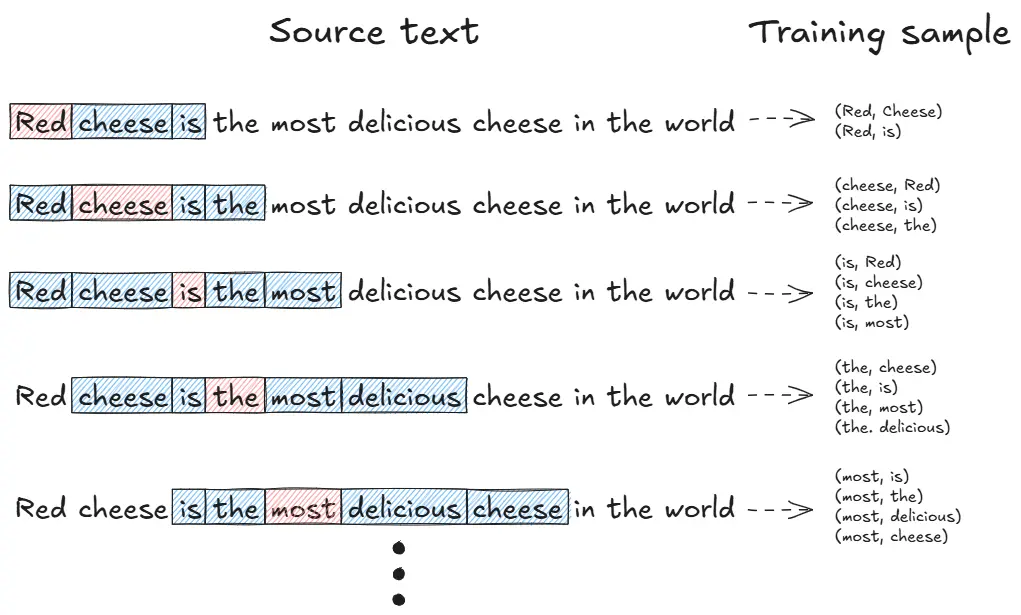

This is one topic that we didn’t talk about extensively so let’s go over it, because that is where the true beauty of GPT lies. How to train over huge amounts of data.

We will build iteratively, first starting small. And going massive as we approach the GPT paper.

This blog helped me with this section.

Preparing the data

The original Transformer was trained for neural machine translation using English-German sentence pairs. The data preparation involves several crucial steps:

# Data preparation

import torch

from torch.utils.data import DataLoader, Dataset

from torch.nn.utils.rnn import pad_sequence

def prepare_training_data(sentences):

# 1. Add special tokens

processed_sentences = []

for sentence in sentences:

processed_sentences.append("<START> " + sentence + " <EOS>")

# 2. Create vocabulary

vocab = build_vocab(processed_sentences)

vocab_size = len(vocab)

# 3. Convert to tensor sequences

sequences = []

for sentence in processed_sentences:

tokens = sentence.split()

sequence = torch.tensor([vocab[token] for token in tokens])

sequences.append(sequence)

# 4. Pad sequences

padded_sequences = pad_sequence(sequences, batch_first=True, padding_value=0)

return padded_sequences, vocab_size

-

Special tokens (

<START>and<EOS>): These tell the model where sentences begin and end. The<START>token signals the decoder to begin generation, while<EOS>teaches it when to stop. Without these, the model wouldn’t know sentence boundaries. As we will move through the years, we will see how the special tokens used in LLMs have evolved as well. For example, think what will happen inside an LLM when it encounters a token that it hasn’t seen during training, like a chinese character etc. -

Vocabulary creation: The vocabulary maps every unique word/token in the training data to a number. This is how we convert text (which computers can’t process) into numerical tensors (which they can). The vocabulary size determines the final layer dimension of our model.

-

Tensor conversion: Neural networks work with numbers, not words. Each word gets replaced by its vocabulary index, creating sequences of integers that can be fed into the model.

-

Padding: Sentences have different lengths, but neural networks need fixed-size inputs for batch processing. Padding with zeros makes all sequences the same length, enabling efficient parallel computation.

Key Training Innovations

The Transformer introduced several training techniques that became standard:

Teacher Forcing with Masking

# During training, decoder sees target sequence shifted by one position

encoder_input = source_sequence

decoder_input = target_sequence[:, :-1] # Remove last token

decoder_output = target_sequence[:, 1:] # Remove first token

# Look-ahead mask prevents seeing future tokens

def create_look_ahead_mask(seq_len):

mask = torch.triu(torch.ones(seq_len, seq_len), diagonal=1)

return mask.bool()

mask = create_look_ahead_mask(decoder_input.size(1))

Why this works: Teacher forcing trains the decoder to predict the next token given all previous tokens, without requiring separate training data. The input-output shift creates a “next token prediction” task from translation pairs. The look-ahead mask ensures the model can’t “cheat” by seeing future tokens during training - it must learn to predict based only on past context, just like during real inference.

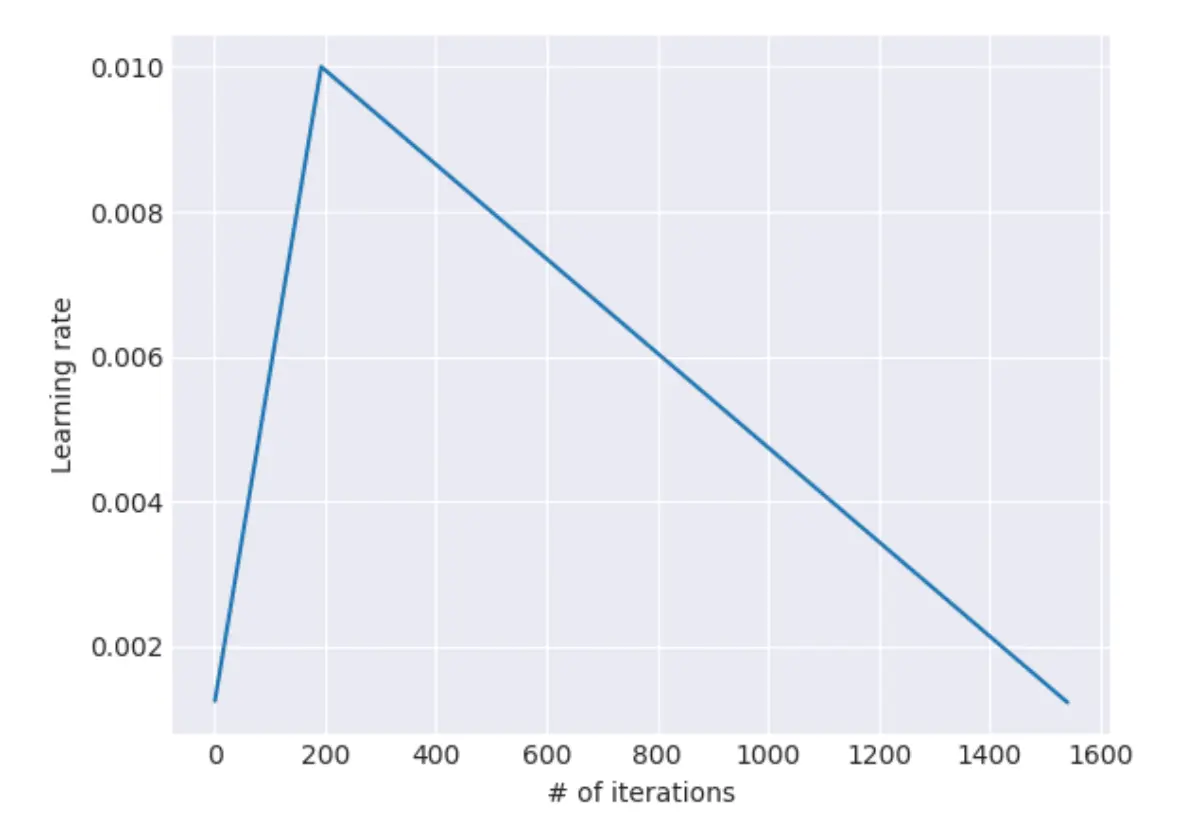

Custom Learning Rate Schedule The paper introduced a specific learning rate scheduler that warms up then decays:

# Learning rate schedule from the paper

import math

class TransformerLRScheduler:

def __init__(self, optimizer, d_model=512, warmup_steps=4000):

self.optimizer = optimizer

self.d_model = d_model

self.warmup_steps = warmup_steps

self.step_count = 0

def step(self):

self.step_count += 1

lr = self.get_lr()

for param_group in self.optimizer.param_groups:

param_group['lr'] = lr

def get_lr(self):

arg1 = self.step_count ** -0.5

arg2 = self.step_count * (self.warmup_steps ** -1.5)

return (self.d_model ** -0.5) * min(arg1, arg2)

Why this schedule: The warmup phase gradually increases the learning rate, preventing the model from making drastic weight updates early in training when gradients are noisy. After warmup, the learning rate decays proportionally to the square root of the step number, allowing for fine-tuning as training progresses. This schedule was crucial for training stability with the Transformer’s deep architecture.

Padding Masks for Loss Computation

import torch.nn.functional as F

def masked_loss(target, prediction, pad_token=0):

# Don't compute loss on padding tokens

mask = (target != pad_token).float()

# Reshape for cross entropy

prediction = prediction.view(-1, prediction.size(-1))

target = target.view(-1)

mask = mask.view(-1)

# Compute cross entropy loss

loss = F.cross_entropy(prediction, target, reduction='none')

masked_loss = loss * mask

return masked_loss.sum() / mask.sum()

Why masking matters: Padding tokens (zeros) are artificial - they don’t represent real words. Computing loss on them would teach the model incorrect patterns and waste computational resources. The mask ensures we only compute loss on actual content, leading to more meaningful gradients and better learning. This also prevents the model from learning to predict padding tokens, which would be useless during inference.

Training Configuration

The original paper used these hyperparameters:

- Model size: 512 dimensions (base model)

- Attention heads: 8

- Encoder/Decoder layers: 6 each

- Feed-forward dimension: 2048

- Dropout: 0.1

- Optimizer: Adam with custom learning rate schedule

- Training time: ~12 hours on 8 P100 GPUs

The Training Loop

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

from torch.optim import Adam

def train_step(model, optimizer, scheduler, encoder_input, decoder_input, decoder_output):

model.train()

optimizer.zero_grad()

# Forward pass

prediction = model(encoder_input, decoder_input)

# Compute masked loss and accuracy

loss = masked_loss(decoder_output, prediction)

accuracy = masked_accuracy(decoder_output, prediction)

# Backward pass

loss.backward()

optimizer.step()

scheduler.step()

return loss.item(), accuracy.item()

# Main training loop

model = TransformerModel(src_vocab_size, tgt_vocab_size, d_model=512)

optimizer = Adam(model.parameters(), lr=1e-3, betas=(0.9, 0.98), eps=1e-9)

scheduler = TransformerLRScheduler(optimizer, d_model=512)

for epoch in range(num_epochs):

for batch in dataloader:

src_batch, tgt_batch = batch

# Prepare inputs

encoder_input = src_batch[:, 1:] # Remove START token

decoder_input = tgt_batch[:, :-1] # Remove EOS token

decoder_output = tgt_batch[:, 1:] # Remove START token

loss, accuracy = train_step(

model, optimizer, scheduler,

encoder_input, decoder_input, decoder_output

)

if step % 100 == 0:

print(f'Epoch {epoch}, Step {step}, Loss: {loss:.4f}, Acc: {accuracy:.4f}')

Why This Training Approach Worked

- Parallelization: Unlike RNNs, all positions could be computed simultaneously

- Stable Gradients: Layer normalization and residual connections prevented vanishing gradients

- Efficient Attention: Scaled dot-product attention was computationally efficient

- Smart Masking: Prevented information leakage while enabling parallel training

This training methodology laid the groundwork for scaling to the massive language models we see today. The key insight was that with proper masking and attention mechanisms, you could train much larger models much faster than sequential architectures allowed.

While the original Transformer showed the power of attention-based training, it was still limited to translation tasks with paired data. The real revolution came when researchers realized they could use similar training techniques on massive amounts of unlabeled text data - setting the stage for GPT and the era of large language models.

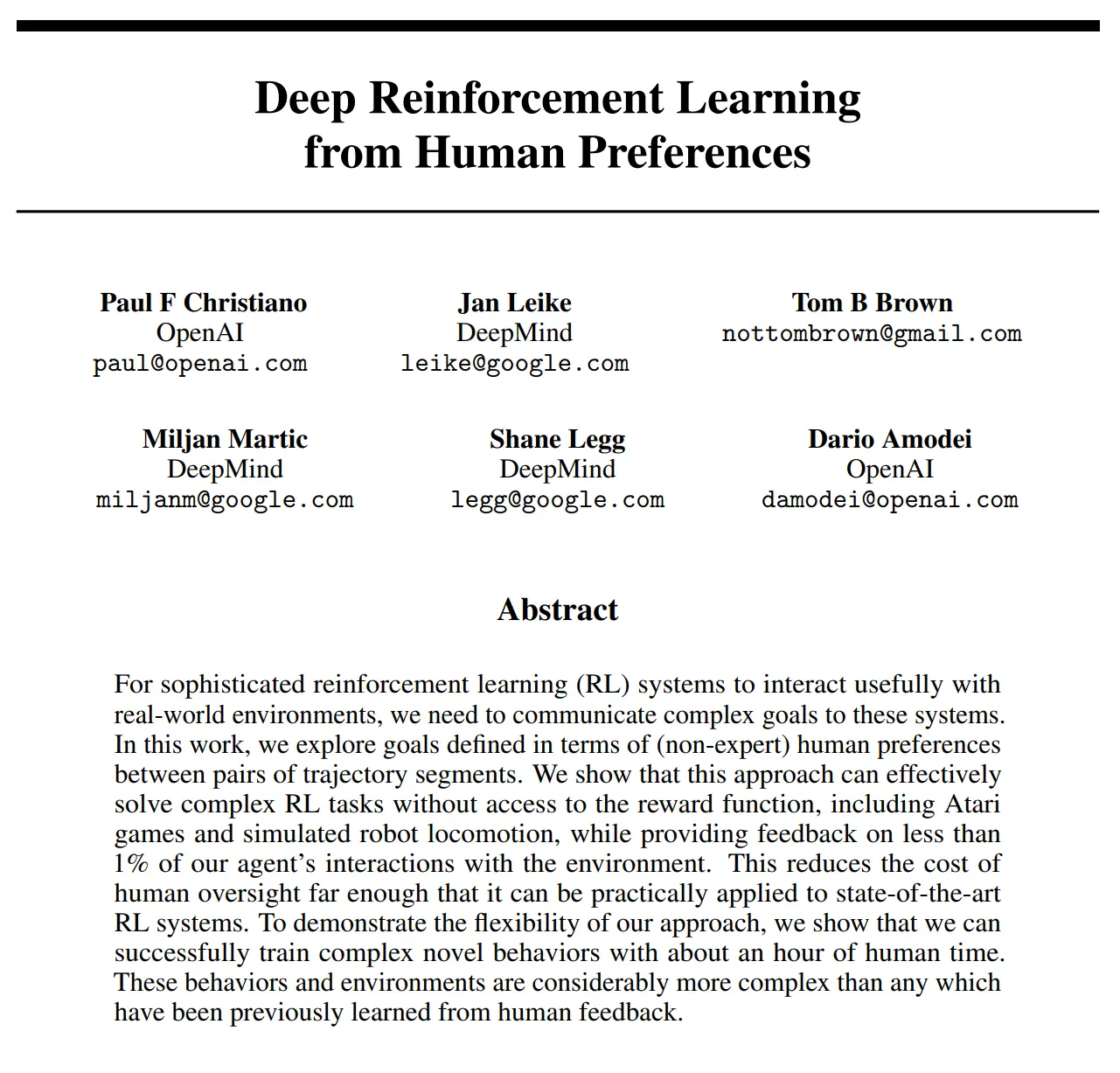

RLHF - Reinforcement Learning from Human Preferences

Link to paper: Deep reinforcement learning from human preferences

Link to implementation: [WORK IN PROGRESS]

Quick Summary

This paper presents a method for training reinforcement learning (RL) agents using human feedback instead of explicitly refined reward functions. Here’s a high-level overview:

The authors address a fundamental challenge in RL: for many complex tasks, designing appropriate reward functions is difficult or impossible. Instead of requiring engineers to craft these functions, they develop a system where:

- Humans compare short video clips of agent behavior (1-2 seconds)

- These comparisons train a reward predictor model

- The agent optimizes its policy using this learned reward function

Key contributions:

- They show this approach can solve complex RL tasks using feedback on less than 1% of the agent’s interactions

- This dramatically reduces the human oversight required, making it practical for state-of-the-art RL systems

- They demonstrate training novel behaviors with just about an hour of human time

- Their approach works across domains including Atari games and simulated robot locomotion

The technique represents a significant advance in aligning AI systems with human preferences, addressing concerns about misalignment between AI objectives and human values. By having humans evaluate agent behavior directly, the system learns rewards that better capture what humans actually want.

As mind boggling as it sounds, the famed algorithm RLHF came out in 2017, the same year attention is all you need came out. Let us understand the ideas put forth and why it was such a big deal.

(If you are not familiar with the idea of RL, I will recommend checking this small course by HuggingFace out)

Problem

Designing reward functions for complex behaviors is nearly impossible. How do you mathematically define “write a helpful response” or “be creative but truthful”? Traditional RL requires explicit numerical rewards for every action, but many desirable behaviors are subjective and context-dependent.

For example, it’s impossible to write code that scores joke quality, but humans can easily compare two jokes and say which is funnier.

Solution :

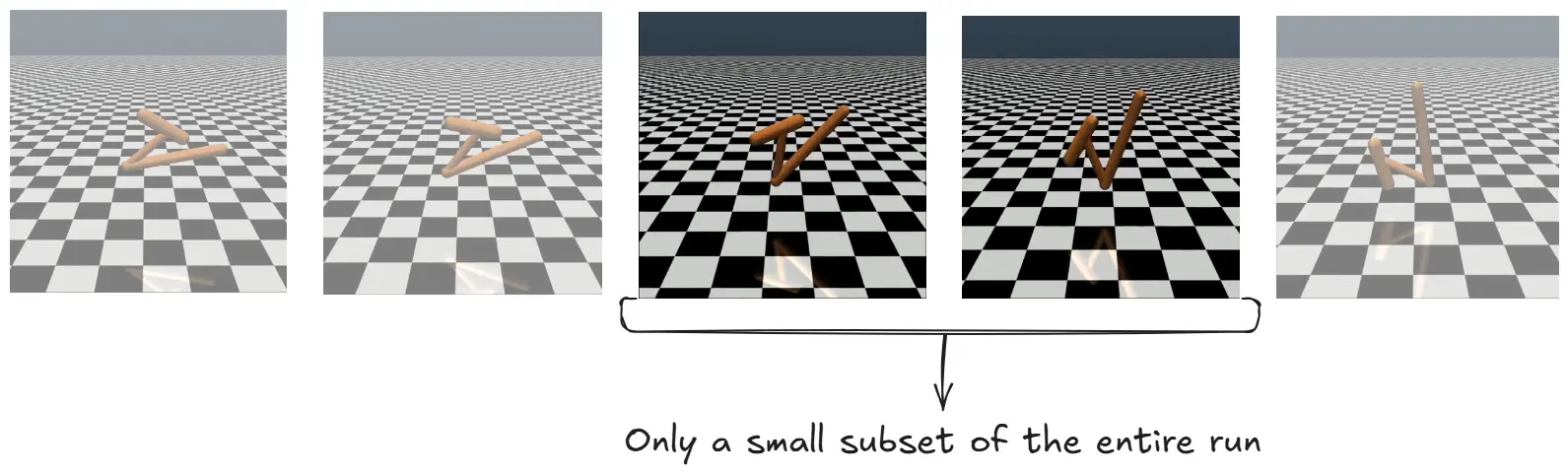

One possible solution is to allow a human to provide feedback on the agents’s current behavior and use this feedback to define the task. But this poses another problem, this would require hundreds of hours as well as domain experience. It was discovered by the researchers that preference modeling by a human even on a small subset provided great results.

An ideal solution will

- Enable us to solve tasks about which we can tell the desired behavior but not necessarily demonstrate or describe it.

- Allows systems to learn from non-expert users

- Scales to large problems

- Is economical

In their experiment, the researchers asked labellers to compare short video clips of the agent’s behavior. They found that by using a small sample of clips they were able to train the system to behave as desired.

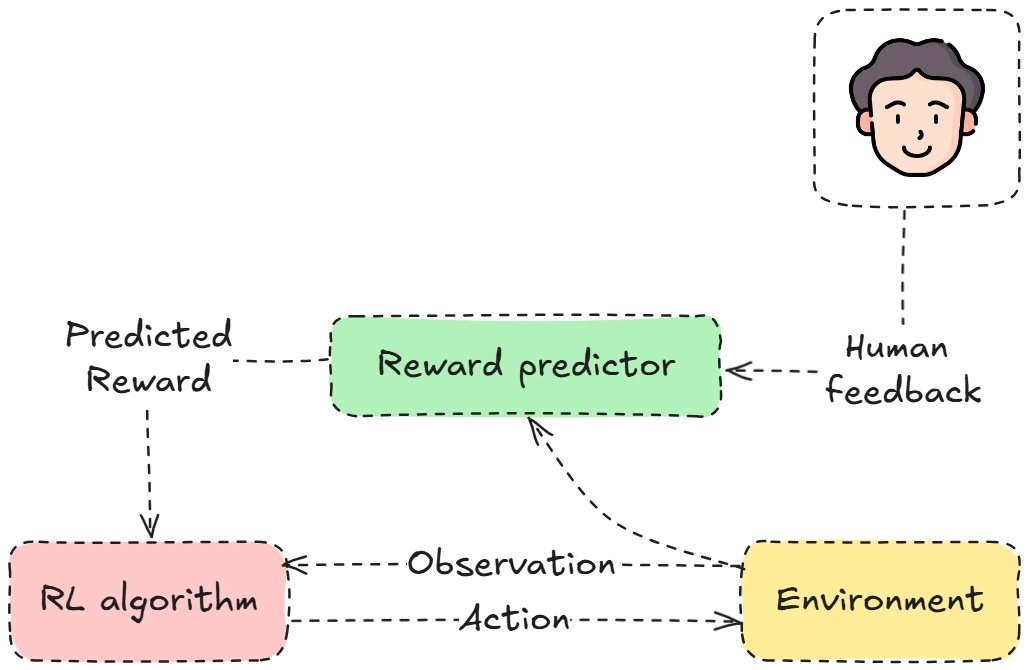

Image sourced from paper

Image sourced from paper

The human observes the agent acting in the environment he then gives he’s feedback. Which is taken by reward predictor which numerical defines the reward. Which is sent to the RL algorithm this updates the agent based on the feedback and observation from the environment. That then changes the action of the agent.

This sounds simple enough in principle, but how do you teach a model to learn from these preferences. I.e reward modeling.

Note: We will be talking more in depth about RL algorithms in the next section. The topics in RL are rather complicated and usually talked in the end after an LLM is trained. So you can skip this part for now if it is daunting.

Reward predictor in RLHF

The following blogs helped me while writing this section

The reward predictor is trained to predict which of two given trajectories(σ¹, σ²) will be preferred by a human

Example:

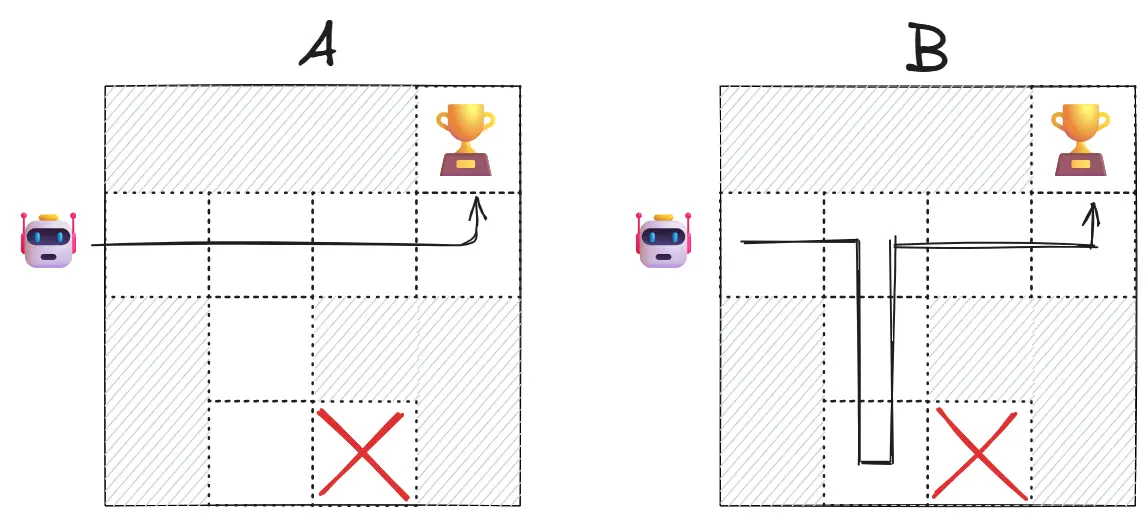

Imagine two robot trajectories:

- Trajectory A: Robot goes directly to the goal

- Trajectory B: Robot roams around then goes to the goal

A human would prefer A (more efficient). The reward model learns to assign higher values to the observation-action pairs in trajectory A, eventually learning that “efficient movement” correlates with human preference.

Reward predictor equation

\[\hat{P}\left[\sigma^{1} \succ \sigma^{2}\right]=\frac{\exp \sum \hat{r}\left(o_{t}^{1}, a_{t}^{1}\right)}{\exp \sum \hat{r}\left(o_{t}^{1}, a_{t}^{1}\right)+\exp \sum \hat{r}\left(o_{t}^{2}, a_{t}^{2}\right)}\]It is trained using cross-entropy loss to match human preferences:

\[\operatorname{loss}(\hat{r})=-\sum_{\left(\sigma^{1}, \sigma^{2}, \mu\right) \in D} \mu(1) \log \hat{P}\left[\sigma^{1} \succ \sigma^{2}\right]+\mu(2) \log \hat{P}\left[\sigma^{2} \succ \sigma^{1}\right]\]Mathematical Notation

- $\hat{P}\left[\sigma^{1} \succ \sigma^{2}\right]$: Predicted probability that trajectory segment $\sigma^{1}$ is preferred over trajectory segment $\sigma^{2}$

- $\hat{r}$: The learned reward function

- $o_{t}^{i}$: Observation at time $t$ in trajectory segment $i$

- $a_{t}^{i}$: Action at time $t$ in trajectory segment $i$

- $\sigma^{i}$: Trajectory segment $i$ (a sequence of observation-action pairs)

- $\exp$: Exponential function

- $\sum$: Summation over all timesteps in the trajectory segment

- $\operatorname{loss}(\hat{r})$: Cross-entropy loss function for the reward model

- $D$: Dataset of human preference comparisons

- $\mu$: Distribution over ${1,2}$ indicating human preference

- $\mu(1)$: Probability that human preferred segment 1

- $\mu(2)$: Probability that human preferred segment 2

- $\log$: Natural logarithm

Let us understand the Reward Function Fitting Process

The Preference-Predictor Model

The authors instead of directly creating a reward function (which rewards an agent when it does the desired behavior and punishes otherwise), they created a preference predictor. Which predicts which of the two given sequence of actions will be preferred by a human.

The Mathematical Formulation (Equation 1)

The equation P̂[σ¹ ≻ σ²] represents the predicted probability that a human would prefer trajectory segment σ¹ over segment σ².

Breaking down the formula:

- $\sigma^{[1]}$ and $\sigma^{[2]}$ are two different trajectory segments (short video clips of agent behavior)

- $o_{t}^{[i]}$ and $a_{t}^{[i]}$ represent the observation and action at time $t$ in trajectory $i$

- $\hat{r}(o_{t}^{[i]}, a_{t}^{[i]})$ is the estimated reward for that observation-action pair

- The formula uses the softmax function (exponential normalization):

This means:

- Sum up all the predicted rewards along trajectory 1

- Sum up all the predicted rewards along trajectory 2

- Apply exponential function to both sums

- The probability of preferring trajectory 1 is the ratio of exp(sum1) to the total exp(sum1) + exp(sum2)

The Loss Function

The goal is to find parameters for r̂ that make its predictions match the actual human preferences:

\[\operatorname{loss}(\hat{r}) = -\sum_{\left(\sigma^{[1]}, \sigma^{[2]}, \mu\right) \in D} \left[\mu([1])\log \hat{P}\left[\sigma^{[1]} \succ \sigma^{[2]}\right] + \mu([2])\log \hat{P}\left[\sigma^{[2]} \succ \sigma^{[1]}\right]\right]\]Where:

- $\left(\sigma^{[1]}, \sigma^{[2]}, \mu\right) \in D$ means we’re summing over all the comparison data in our dataset $D$

- $\mu$ is a distribution over ${1,2}$ indicating which segment the human preferred

- If the human strictly preferred segment 1, then $\mu([1]) = 1$ and $\mu([2]) = 0$

- If the human strictly preferred segment 2, then $\mu([1]) = 0$ and $\mu([2]) = 1$

- If the human found them equal, then $\mu([1]) = \mu([2]) = 0.5$

This is the standard cross-entropy loss function used in classification problems, measuring how well our predicted probabilities match the actual human judgments.

Consider reading this beautiful blog on Entropy by Christopher Olah, if you wish to gain a deeper understanding of cross-entropy.

The Bradley-Terry Model Connection

Note from Wikipedia: The Bradley–Terry model is a probability model for the outcome of pairwise comparisons between items, teams, or objects. Given a pair of items $i$ and $j$ drawn from some population, it estimates the probability that the pairwise comparison $i > j$ turns out true, as

\[\Pr(i>j) = \frac{p_i}{p_i + p_j}\]where $p_i$ is a positive real-valued score assigned to individual $i$. The comparison $i > j$ can be read as “i is preferred to j”, “i ranks higher than j”, or “i beats j”, depending on the application.

This approach is based on the Bradley-Terry model, which is a statistical model for paired comparisons. It’s similar to:

-

The Elo rating system in chess: Players have ratings, and the difference in ratings predicts the probability of one player beating another.

-

In this case: Trajectory segments have “ratings” (the sum of rewards), and the difference in ratings predicts the probability of a human preferring one segment over another.

In essence, the reward function learns to assign higher values to states and actions that humans tend to prefer, creating a preference scale that can be used to guide the agent’s behavior.

The most important breakthrough: We can align AI systems with human values using comparative feedback from non-experts. This insight would prove crucial when training language models - instead of trying to define “helpful” or “harmless” mathematically, we can simply ask humans to compare outputs.

This comparative approach scales much better than rating individual responses, making it practical for training large language models on human preferences.

| Fun story: One time researchers tried to RL a helicopter and it started flying backwards |

PPO: Proximal Policy Optimization

Link to paper: Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms

Link to implementation: [WORK IN PROGRESS]

Quick Summary

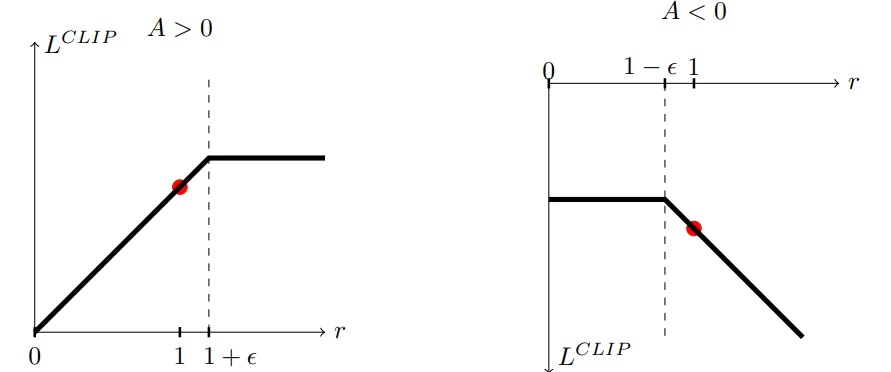

This paper by John Schulman et al. from OpenAI introduces Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), a family of policy gradient methods for reinforcement learning that achieves the reliability and data efficiency of Trust Region Policy Optimization (TRPO) while being much simpler to implement and more compatible with various neural network architectures.

Key contributions:

- A novel “clipped” surrogate objective function that provides a pessimistic estimate of policy performance

- An algorithm that alternates between data collection and multiple epochs of optimization on the same data

- Empirical validation showing PPO outperforms other online policy gradient methods across continuous control tasks and Atari games

- A balance between sample complexity, implementation simplicity, and computation time

The core innovation is their clipped probability ratio approach, which constrains policy updates without requiring the complex second-order optimization techniques used in TRPO. This makes PPO more practical while maintaining performance guarantees.

Another LLM algo that came out in 2017, and that too again by OpenAI. Really goes to show how much they tried to advance AI and be public about it (At least in the early days).

This is going to be math heavy so be prepared (Dw, I will guide you in each step)

Problem

However, there is room for improvement in developing a method that is scalable (to large models and parallel implementations), data efficient, and robust (i.e., successful on a variety of problems without hyperparameter tuning). Q-learning (with function approximation) fails on many simple problems and is poorly understood, vanilla policy gradient methods have poor data effiency and robustness; and trust region policy optimization (TRPO) is relatively complicated, and is not compatible with architectures that include noise (such as dropout) or parameter sharing (between the policy and value function, or with auxiliary tasks).

Essentially there were a lot of RL algorithms, but none of them worked efficiently at scale.

Solution

This paper seeks to improve the current state of affairs by introducing an algorithm that attains the data efficiency and reliable performance of TRPO, while using only first-order optimization. We propose a novel objective with clipped probability ratios, which forms a pessimistic estimate (i.e., lower bound) of the performance of the policy. To optimize policies, we alternate between sampling data from the policy and performing several epochs of optimization on the sampled data

The authors found a way to take the best RL algorithm of the time (TRPO) and make it work at scale.

The following blogs & articles helped me write this section

- Spinning up docs by OpenAI, consider going through this to help understand the nomenclature used throughout this section

- RL blogs by jonathan hui, they really simplified the ideas for me

- Understanding Policy Gradients, this blog really helped me understand the math behind the idea

- These blogs were extremely helpful too (each word is a different link)

- The bible of modern RL

What is Reinforcement Learning

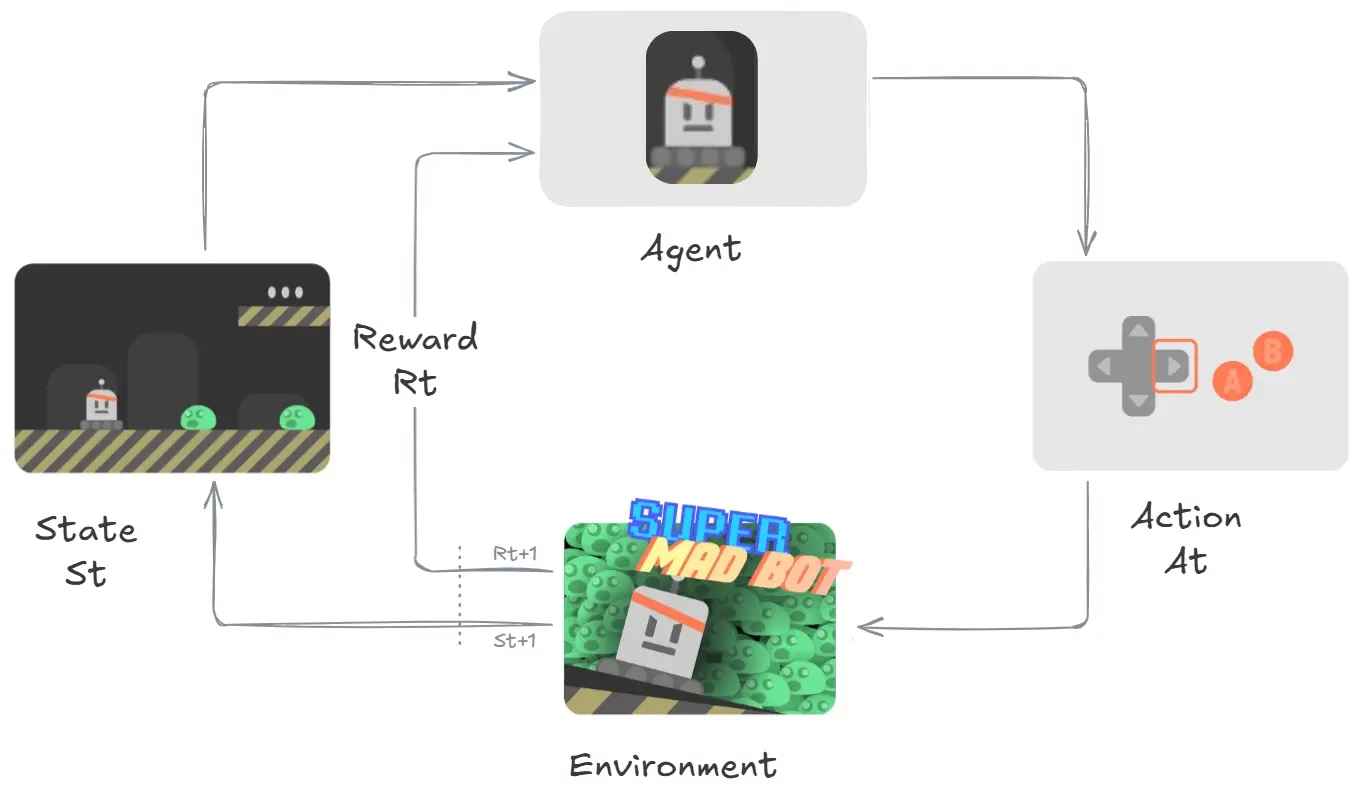

Image taken from HuggingFace Course

Image taken from HuggingFace Course

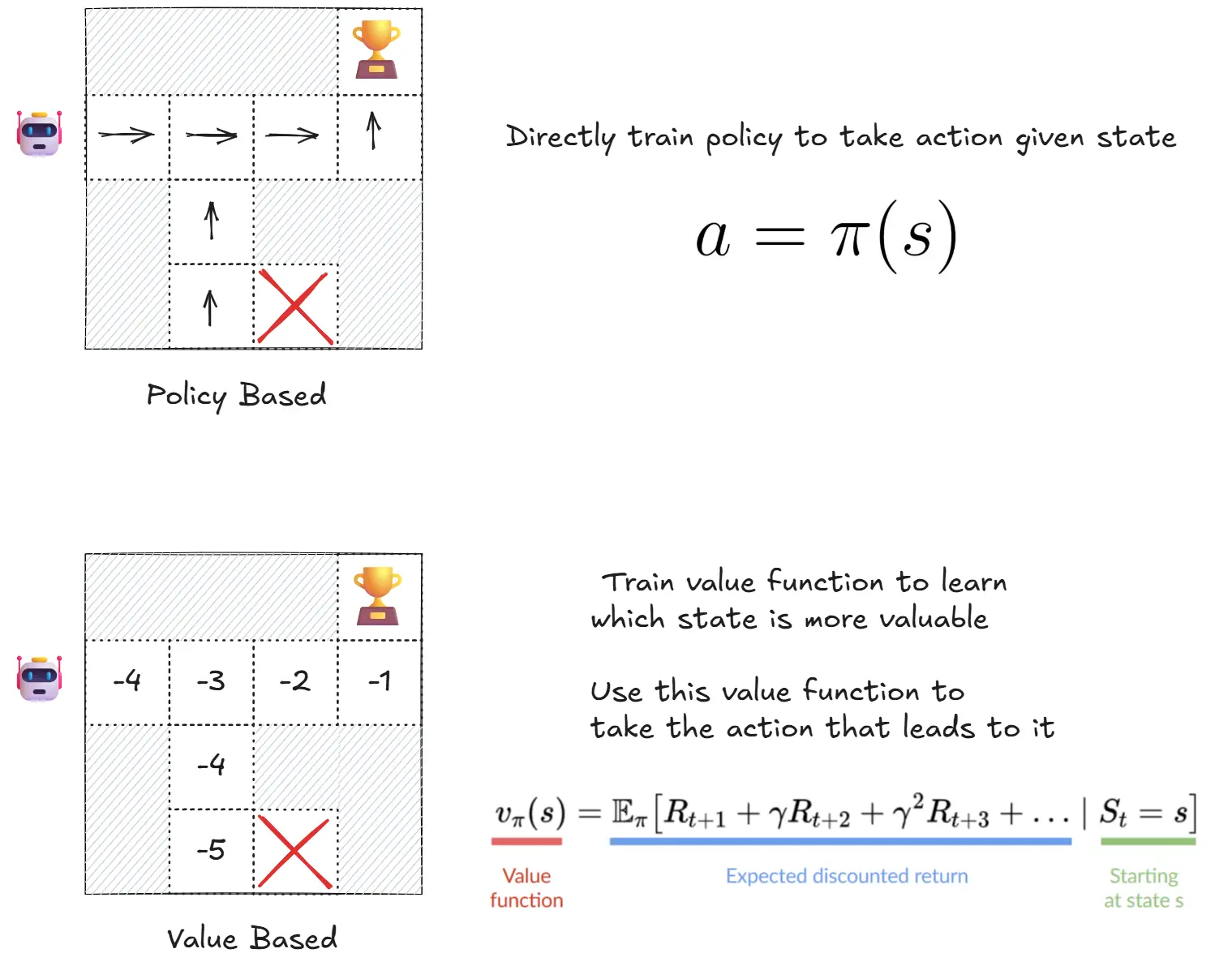

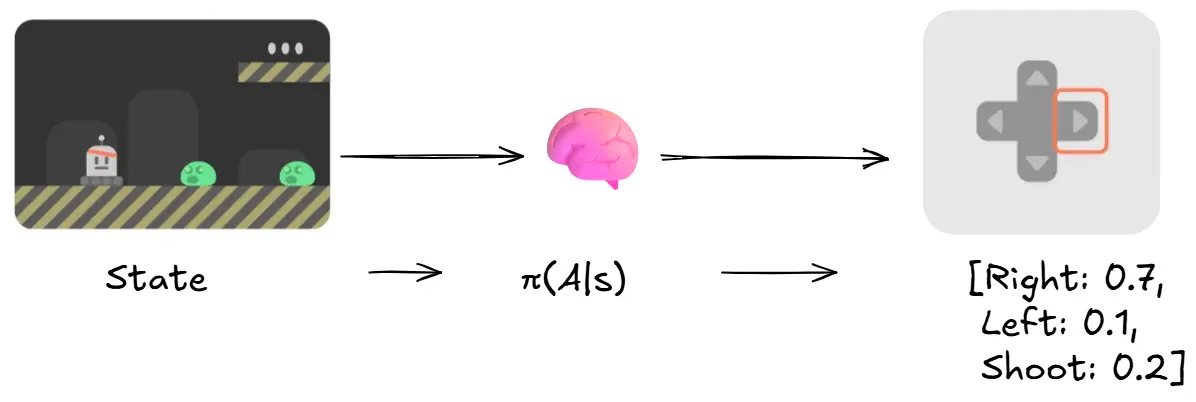

In RL we create an Agent (An ML model like Artificial Neural Network) give it a defined set of Actions $A_t$ (In this case it would be, move left, move right, Press A to shoot).

The agent then chooses an action and interacts with the Environment, which returns a new state as well as reward (positive if we survived or did a favourable outcome, negative if we die or do an unfavourable outcome).

Step by Step it looks something like this:

- The agent recieves state $S_0$ from the environment (In this that would be the first frame of the game)

- Based on state $S_0$, the agent takes action $A_0$ (chooses to move right)

- The environment goes to new frame, new state $S_1$.

- The environment gives the agent, reward $R_t$ (still alive!!!).

The idea behind RL is based on reward hypothesis, which states that

| All goals can be described as the maximization of the expected return (expected cumulative reward) |

Which can be mathematically represented as $R(\tau) = r_{t+1} + r_{t+2} + r_{t+3} + r_{t+4} + \ldots$ ($\tau$ read as tau)

Remember this, It will prove useful later.

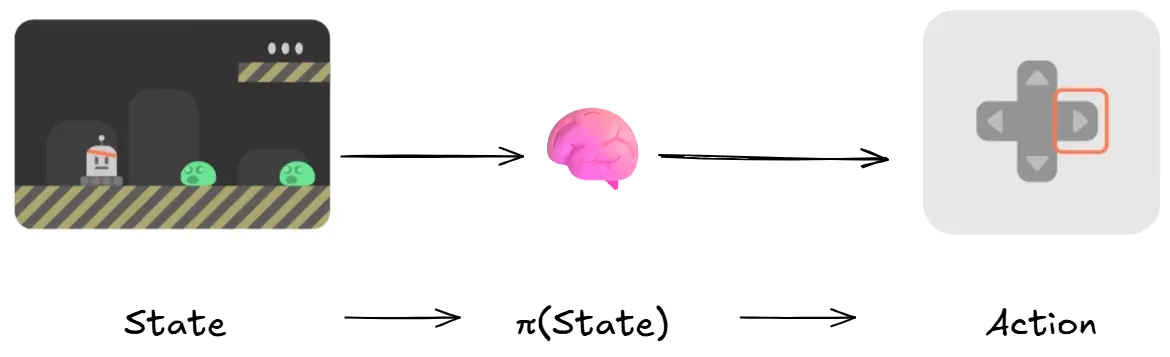

Policy π: The Agent’s Brain

The Policy π is the brain of our Agent, it’s the function that tells an Agent what action it should take at a given state and time.

The policy is what we want to train and make an optimum policy π*, that maximizes expected return when the agent acts according to it. (remember that is the idea behind RL)

Image taken from OpenAI Spinning Up

Image taken from OpenAI Spinning Up

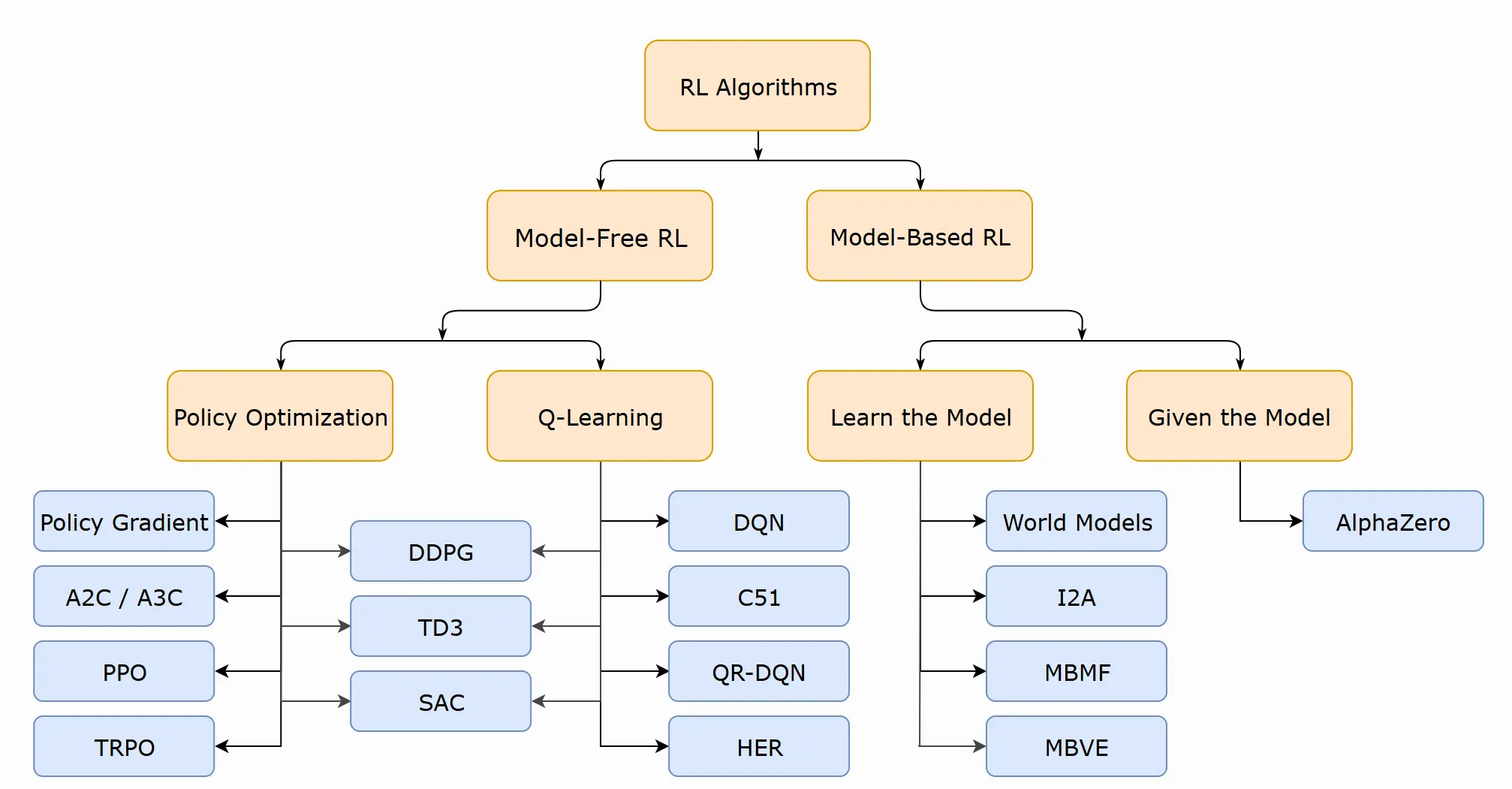

There are many RL algorithms present that we can use to train the policy as you can see from the image above, But most of them are developed from two central methods:

- Policy based methods : Directly, by teaching the agent to learn which action to take, given the current state

- Value based methods : Indirectly, teach the agent to learn which state is more valuable and then take the action that leads to the more valuable states

Image taken from HuggingFace Course

Image taken from HuggingFace Course

(Don’t get scared by the equations, I will explain them as we move forward. Also, this was a quick recap of RL, for a better deep dive. Consider going through the HF course)

As this section is dedicated to PPO, I will primarily be talking about the topics concerned with it. It can broadly be put in the following order:

- Policy Gradient Methods

- TRPO

- PPO

I am skipping over many other interesting and amazing algorithms like Q-Learning, DQN, Actor-critic etc. As they are not relevant to this section. I still implore you to explore them through the links I have provided to get a better, broader and deeper grasp of RL.

Before we move to the next section, I want to talk about a question that baffled me when I started learning about RL.

“Why do we need a value based approach”

Policy based approach seem to work great and are intuitive as well, given a state, choose an action. Then why do we use value based approaches. Needless complexity. Think for a minute then see the answer

Answer

Value-based methods shine in scenarios where policy-based methods struggle:

1. Discrete Action Spaces with Clear Optimal Actions In environments like Atari games or grid worlds, there’s often a single best action for each state. Value-based methods (like DQN) can directly learn which action has the highest expected return, making them sample-efficient for these deterministic scenarios.

2. Exploration Efficiency Value functions provide natural exploration strategies. Methods like ε-greedy or UCB can systematically explore based on value estimates. Policy methods often struggle with exploration, especially in sparse reward environments where random policy perturbations rarely discover good behavior.

3. Off-Policy Learning Value-based methods can learn from any data - even old experiences stored in replay buffers. This makes them incredibly sample-efficient. Policy methods traditionally required on-policy data, though modern techniques like importance sampling have bridged this gap.

4. Computational Efficiency In discrete action spaces, value-based methods often require just one forward pass to select an action (argmax over Q-values). Policy methods might need to sample from complex probability distributions or solve optimization problems.

Where Policy Methods Fail:

- High-dimensional discrete actions: Computing argmax becomes intractable

- Continuous control: You can’t enumerate all possible actions to find the maximum

- Stochastic optimal policies: Sometimes the best strategy is inherently random (like rock-paper-scissors), which value methods can’t represent directly

The truth is, both approaches are complementary tools for different types of problems.

Policy Gradient Methods

Policy gradient methods directly optimize a policy function by adjusting its parameters in the direction of greater expected rewards. They work by:

- Collecting experience (state-action pairs and rewards) using the current policy

- Estimating the policy gradient (the direction that would improve the policy)

- Updating the policy parameters using this gradient

The Gradient Estimator

In our discussion so far, we talked about deterministic policy based methods. Ie given a state, choose an action $\pi(s) = a$. But when we are talking about policy gradients, we use a stochastic policy based method. Ie given a state, return a probability distribution of actions $\pi(a|s) = P[A|s]$.

We also need to be aware of a few terms and mathematical tricks before moving forward:

-

Trajectory: A series of state action pair is called a trajectory.

\[\tau = (s_1,a_1,s_2,a_2,\ldots,s_H,a_H)\] -

Log derivative trick:

\[\nabla_\theta \log z = \frac{1}{z} \nabla_\theta z\]This trick allows us to convert the gradient of a probability into the gradient of its logarithm, which is computationally more stable and easier to work with.

(To derive it just apply chain rule and know that the derivative of $\log(x)$ = $1/x$)

-

Definition of Expectation:

For discrete distributions: \(\mathbb{E}_{x \sim p(x)}[f(x)] = \sum_x p(x)f(x) \tag{1}\)

For continuous distributions: \(\mathbb{E}_{x \sim p(x)}[f(x)] = \int_x p(x)f(x) \, dx \tag{2}\)

If you are new to the idea of expectation, Consider checking this amazing blog on the topic.

Deriving the Policy Gradient

Let $\tau$ be a trajectory (sequence of state-action pairs), $\theta$ be the weights of our neural network policy. Our policy $\pi_\theta$ outputs action probabilities that depend upon the current state and network weights.

We begin with the reward hypothesis: we want to maximize $R(\tau)$ where $\tau$ is a trajectory.

We can write the objective as the probability of a trajectory being chosen by the policy multiplied by the reward for that trajectory:

\[J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim \pi_\theta}[R(\tau)] = \sum_\tau \pi_\theta(\tau)R(\tau)\]This formulation is crucial because it connects:

- $\pi_\theta(\tau)$: How likely our current policy is to generate trajectory $\tau$

- $R(\tau)$: How much reward we get from that trajectory

For continuous trajectory spaces, we can write this as:

\[J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim \pi_\theta}[R(\tau)] = \int \pi_\theta(\tau)R(\tau)d\tau\]Now we can derive the policy gradient by taking the gradient of our objective:

\[\nabla_\theta J(\theta) = \nabla_\theta \int \pi_\theta(\tau)R(\tau)d\tau \tag{3}\] \[= \int \nabla_\theta \pi_\theta(\tau)R(\tau)d\tau \tag{4}\] \[= \int \pi_\theta(\tau) \frac{\nabla_\theta \pi_\theta(\tau)}{\pi_\theta(\tau)} R(\tau)d\tau \tag{5}\] \[= \int \pi_\theta(\tau) \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(\tau) R(\tau)d\tau \tag{6}\] \[= \mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim \pi_\theta}[\nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(\tau) R(\tau)] \tag{7}\]Step-by-step explanation:

- (3) Start with gradient of our objective function

- (4) Push gradient inside the integral

- (5) Multiply and divide by $\pi_\theta(\tau)$

- (6) Apply the log derivative trick: $\nabla_\theta \log(z) = \frac{1}{z} \nabla_\theta z$

- (7) Convert back to expectation form

The trajectory probability factors as: \(\pi_\theta(\tau) = \prod_{t=0}^{T} \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t)\)

So the log probability becomes: \(\log \pi_\theta(\tau) = \sum_{t=0}^{T} \log \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t)\)

What does this mean for us? If you want to maximize your expected reward, you can use gradient ascent. The gradient of the expected reward has an elegant form - it’s simply the expectation of the trajectory return times the sum of log probabilities of actions taken in that trajectory.

In reinforcement learning, a trajectory $\tau = (s_1, a_1, s_2, a_2, \ldots, s_T, a_T)$ is generated through a sequential process. The probability of observing this specific trajectory under policy $\pi_\theta$ comes from the chain rule of probability.

| This is quite complex to intuitively understand in my opinion. Consider going through this stack exchange. Intuition: Let’s calculate the joint probability of a sequence like $P(\text{sunny weather, white shirt, ice cream})$ - what’s the chance it’s sunny outside, I’m wearing a white shirt, and I chose to eat ice cream all happening together? We can break this down step by step: First, what’s the probability it’s sunny outside? That’s $P(\text{sunny})$. Given that it’s sunny, what are the chances I wear a white shirt? That’s $P(\text{white shirt | sunny})$. Finally, given it’s sunny and I’m wearing white, what’s the probability I eat ice cream? That’s $P(\text{ice cream | sunny, white shirt})$. \(P(\text{sunny, white shirt, ice cream}) = P(\text{sunny}) \cdot P(\text{white shirt | sunny}) \cdot P(\text{ice cream | sunny, white shirt})\) By multiplying these conditional probabilities, we get the full joint probability. In reinforcement learning, trajectories work the same way: $P(s_1, a_1, s_2, a_2, \ldots)$ breaks down into “what state do we start in?” then “what action do we take?” then “where do we transition?” and so on. Each step depends only on what happened before, making complex trajectory probabilities manageable to compute and optimize. |

The joint probability of a sequence of events can be factored as: \(P(s_1, a_1, s_2, a_2, \ldots, s_T, a_T) = P(s_1) \cdot P(a_1|s_1) \cdot P(s_2|s_1, a_1) \cdot P(a_2|s_1, a_1, s_2) \cdots\)

However, in the Markov Decision Process (MDP) setting, we have two key assumptions:

- Markov Property: Next state depends only on current state and action: $P(s_{t+1}|s_1, a_1, \ldots, s_t, a_t) = P(s_{t+1}|s_t, a_t)$

- Policy Markov Property: Action depends only on current state: $P(a_t|s_1, a_1, \ldots, s_t) = \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t)$

| Chapter 3 of RL book by Sutton and Barto covers the topic well |

Applying these assumptions:

\[\pi_\theta(\tau) = \pi_\theta(s_1, a_1, \ldots, s_T, a_T) = p(s_1) \prod_{t=1}^{T} \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t)p(s_{t+1}|s_t, a_t)\] \[\underbrace{p(s_1) \prod_{t=1}^{T} \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t)p(s_{t+1}|s_t, a_t)}_{\pi_\theta(\tau)}\]- $p(s_1)$: Initial state distribution (environment dependent)

- $\pi_\theta(a_t|s_t)$: Policy probability of choosing action $a_t$ in state $s_t$

- $p(s_{t+1}|s_t, a_t)$: Environment transition probability (environment dependent)

When we take the log of a product, it becomes a sum:

\[\log \pi_\theta(\tau) = \log p(s_1) + \sum_{t=1}^{T} \log \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t) + \sum_{t=1}^{T} \log p(s_{t+1}|s_t, a_t)\]The first and last terms do not depend on $\theta$ and can be removed when taking gradients(and this is often done in practice):

- $\log p(s_1)$: Initial state is determined by environment, not our policy

- $\log p(s_{t+1}|s_t, a_t)$: Environment dynamics don’t depend on our policy parameters

Therefore: \(\nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(\tau) = \nabla_\theta \sum_{t=1}^{T} \log \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t) = \sum_{t=1}^{T} \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t)\)

So the policy gradient: \(\nabla_\theta J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim \pi_\theta}[\nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(\tau) R(\tau)]\)

becomes: \(\nabla_\theta J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim \pi_\theta}\left[\left(\sum_{t=1}^{T} \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t)\right) R(\tau)\right]\)

The trajectory return $R(\tau)$ is the total reward collected along the trajectory: \(R(\tau) = \sum_{t=1}^{T} r(s_t, a_t)\)

So our gradient becomes: \(\nabla_\theta J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim \pi_\theta}\left[\left(\sum_{t=1}^{T} \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_t\|s_t)\right) \left(\sum_{t=1}^{T} r(s_t, a_t)\right)\right]\)

How do we compute expectations in practice?

We can’t compute the expectation $\mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim \pi{\theta}}[\cdot]$ analytically because:

- There are infinitely many possible trajectories

- We don’t know the environment dynamics $p(s_{t+1}|s_t, a_t)$

Instead, we use Monte Carlo sampling:

- Collect $N$ sample trajectories by running our current policy: ${\tau_1, \tau_2, \ldots, \tau_N}$

- Approximate the expectation using the sample average:

Applying Monte Carlo approximation

This is a fabulous video to understand Monte Carlo approximation.

Substituting our specific function: \(f(\tau) = \left(\sum_{t=1}^{T} \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t)\right) \left(\sum_{t=1}^{T} r(s_t, a_t)\right)\)

We get: \(\boxed{\nabla_\theta J(\theta) \approx \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} \left(\sum_{t=1}^{T} \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_{i,t}|s_{i,t})\right) \left(\sum_{t=1}^{T} r(s_{i,t}, a_{i,t})\right)}\)

\[\boxed{\theta \leftarrow \theta + \alpha \nabla_\theta J(\theta)}\]Where:

- $i$ indexes the sampled trajectories ($1$ to $N$)

- $t$ indexes time steps within each trajectory ($1$ to $T$)

- $(s_{i,t}, a_{i,t})$ is the state-action pair at time $t$ in trajectory $i$

The elegant result is that we only need gradients of our policy’s action probabilities - the environment dynamics completely disappear from our gradient computation! This makes policy gradients model-free and widely applicable.

And we use this policy gradient to update the policy $\theta$.

To get an intuition behind the idea consider reading the intuition part of this blog.

Policy Gradient for Continuous Space

So far, we’ve been working with discrete action spaces, like our super mad bot game where you can move left, move right, or press A to shoot. But what happens when your agent needs to control a robot arm, steer a car, or even select the “best” next token in language model fine-tuning? Welcome to the world of continuous control!

In discrete spaces, our policy outputs probabilities for each possible action:

- Move left: 30%

- Move right: 45%

- Shoot: 25%

But in continuous spaces, actions are real numbers. Imagine trying to control a robot arm where the joint angle can be any value between -180° and +180°. You can’t enumerate probabilities for every possible angle, there are infinitely many! (like in real numbers, you cannot even count the numbers present between 179 and 180… Where do you even begin?)

The solution is to make our neural network output parameters of a probability distribution (eg mean and standard deviation of a normal distribution) instead of individual action probabilities. Specifically, we use a Gaussian (normal) distribution.

Here’s how it works:

Instead of: $\pi_\theta(a_t|s_t) = \text{[probability for each discrete action]}$

We use: $\pi_\theta(a_t|s_t) = \mathcal{N}(f_{\text{neural network}}(s_t); \Sigma)$

Let’s break it down:

- Feed the state $s_t$ into your neural network

- Network outputs the mean $\mu = f_{\text{neural network}}(s_t)$ - this is the “preferred” action

- Choose a covariance matrix $\Sigma$ - this controls how much exploration/uncertainty around that mean

- Sample the actual action from the Gaussian: $a_t \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu, \Sigma)$

Now comes the amazing part. Remember our policy gradient formula?

\[\nabla_\theta J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim \pi_\theta}\left[\left(\sum_{t=1}^{T} \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t)\right) R(\tau)\right]\]The exact same formula still applies! We just need to compute $\nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t)$ differently.

Let’s start with what a Multivariant Gaussian distribution actually looks like. For continuous actions, we assume they follow this probability density function:

\[f(x) = \frac{1}{(2\pi)^{d/2} |\Sigma|^{1/2}} \exp\left\{-\frac{1}{2}(x - \mu)^T \Sigma^{-1} (x - \mu)\right\}\]This looks scary, but it’s just the mathematical way of saying: “actions are most likely to be near the mean $\mu$, with spread determined by covariance $\Sigma$.”

(To understand where this idea comes from, read 13.7 from RL by Sutton and Barton)

Now, since our policy $\pi_\theta(a_t|s_t) = \mathcal{N}(f_{\text{neural network}}(s_t); \Sigma)$, we have:

\[\log \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t) = \log f(a_t)\]Taking the logarithm of our Gaussian:

\[\log \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t) = \log\left[\frac{1}{(2\pi)^{d/2} |\Sigma|^{1/2}} \exp\left\{-\frac{1}{2}(a_t - \mu)^T \Sigma^{-1} (a_t - \mu)\right\}\right]\]Using properties of logarithms ($\log(AB) = \log A + \log B$ and $\log(e^x) = x$):

\[\log \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t) = \log\left[\frac{1}{(2\pi)^{d/2} |\Sigma|^{1/2}}\right] - \frac{1}{2}(a_t - \mu)^T \Sigma^{-1} (a_t - \mu)\]The first term is just a constant (doesn’t depend on our neural network parameters $\theta$), so we can ignore it when taking gradients:

\[\log \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t) = -\frac{1}{2}(a_t - \mu)^T \Sigma^{-1} (a_t - \mu) + \text{const}\]Since $\mu = f_{\text{neural network}}(s_t)$, we can rewrite this as:

\[\log \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t) = -\frac{1}{2}||f(s_t) - a_t||^2_\Sigma + \text{const}\]Both the above equations are the same, it’s just a shorthand of writing it this way. It is also known as Mahalanobis distance squared.

Now we can compute the gradient with respect to our network parameters $\theta$:

\[\nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t) = \nabla_\theta \left[-\frac{1}{2}(a_t - f(s_t))^T \Sigma^{-1} (a_t - f(s_t))\right]\]Let’s define $u = a_t - f(s_t)$ to simplify notation. Our expression becomes:

\[\nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t) = \nabla_\theta \left[-\frac{1}{2} u^T \Sigma^{-1} u\right]\]Since $a_t$ and $\Sigma^{-1}$ don’t depend on $\theta$, we have:

\[\frac{\partial u}{\partial \theta} = \frac{\partial}{\partial \theta}(a_t - f(s_t)) = -\frac{\partial f(s_t)}{\partial \theta}\]For the quadratic form $u^T \Sigma^{-1} u$, using the chain rule:

\[\frac{\partial}{\partial \theta}(u^T \Sigma^{-1} u) = \frac{\partial u^T}{\partial \theta} \Sigma^{-1} u + u^T \Sigma^{-1} \frac{\partial u}{\partial \theta}\]Since $\Sigma^{-1}$ is symmetric, we can write:

\[\frac{\partial}{\partial \theta}(u^T \Sigma^{-1} u) = 2 u^T \Sigma^{-1} \frac{\partial u}{\partial \theta}\]Substituting back our expressions:

\[\nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t) = -\frac{1}{2} \cdot 2 \cdot u^T \Sigma^{-1} \frac{\partial u}{\partial \theta}\] \[= -u^T \Sigma^{-1} \left(-\frac{\partial f(s_t)}{\partial \theta}\right)\] \[= u^T \Sigma^{-1} \frac{\partial f(s_t)}{\partial \theta}\]Substituting $u = a_t - f(s_t)$ back:

\[\nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t) = (a_t - f(s_t))^T \Sigma^{-1} \frac{\partial f(s_t)}{\partial \theta}\]Since $\Sigma^{-1}$ is symmetric, $(a_t - f(s_t))^T \Sigma^{-1} = \Sigma^{-1}(a_t - f(s_t))$ when treated as a row vector, so we can write:

\[\nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t) = \Sigma^{-1}(a_t - f(s_t)) \frac{\partial f(s_t)}{\partial \theta}\]Rearranging to match the original form:

\[\nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t) = -\Sigma^{-1}(f(s_t) - a_t) \frac{\partial f(s_t)}{\partial \theta}\]This gradient has a beautiful intuitive interpretation:

- $(f(s_t) - a_t)$: The difference between what your network predicted and the action you actually took

- $\frac{df}{d\theta}$: How to change the network parameters to affect the output

- $\Sigma^{-1}$: Weighting factor (less weight for high-variance directions)

When you collect experience and compute rewards, here’s what happens:

- Good action taken ($R(\tau) > 0$): The gradient pushes $f(s_t)$ closer to the good action $a_t$

- Bad action taken ($R(\tau) < 0$): The gradient pushes $f(s_t)$ away from the bad action $a_t$

- Standard backpropagation: This gradient flows back through the network to update $\theta$

Our policy gradient update remains: \(\theta \leftarrow \theta + \alpha \nabla_\theta J(\theta)\)

The only difference is how we compute $\nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t)$:

- Discrete case: Gradient of softmax probabilities

- Continuous case: Gradient of Gaussian log-likelihood (what we just derived!)

Everything else stays identical - collect trajectories, compute returns, update parameters. The same core algorithm seamlessly handles both discrete and continuous control problems!

Policy Gradient Improvements

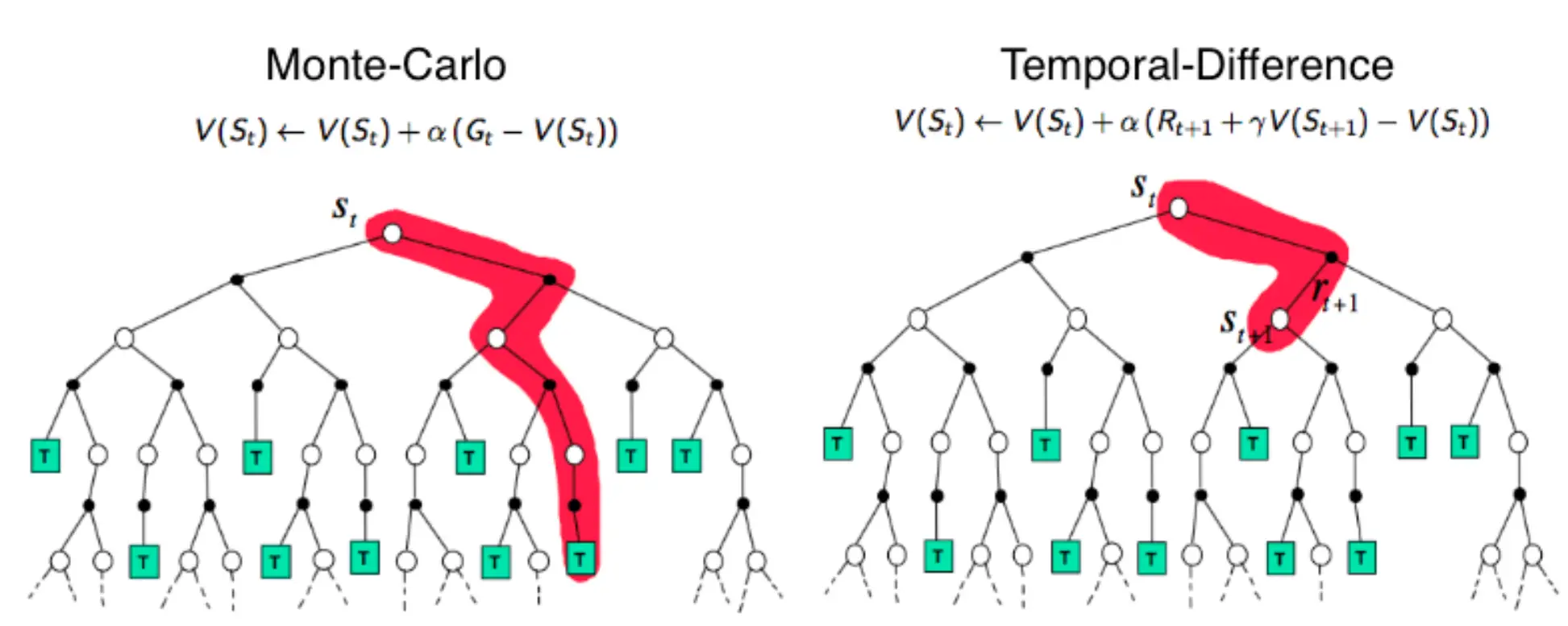

There are two methods in which RL is trained

- Monte Carlo Learning: Cummulative reward of the entire episode (Entire run of the enviorment)

- Temporal Difference Learning: Reward is used to update policy in every step

Image taken from Reinforcement Learning and Bandits for Speech and Language Processing: Tutorial, Review and Outlook

Image taken from Reinforcement Learning and Bandits for Speech and Language Processing: Tutorial, Review and Outlook

Policy Gradient (PG) uses MC this causes it to have low bias (Expected reward is close to actual reward, as the same policy is used throughout the run) but high variance (Some runs produce great results, some really bad).

| A stack exchange on bias & variance in RL |

Remember, our policy gradient formula is:

\[\nabla_\theta J(\theta) \approx \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} \left(\sum_{t=1}^{T} \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_{i,t}|s_{i,t})\right) \left(\sum_{t=1}^{T} r(s_{i,t}, a_{i,t})\right)\]We can rewrite this more compactly as:

\[\nabla_\theta J(\theta) \approx \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} \sum_{t=1}^{T} \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_{i,t}|s_{i,t}) \cdot Q(s_{i,t}, a_{i,t})\]Where $Q(s,a)$ represents the total reward we get from taking action $a$ in state $s$ (this is called the Q-function or action-value function).

The Baseline Trick

Here’s a mathematical insight: we can subtract any term from our gradient as long as that term doesn’t depend on our policy parameters $\theta$.

Why? Because: \(\nabla_\theta [f(\theta) - c] = \nabla_\theta f(\theta) - \nabla_\theta c = \nabla_\theta f(\theta) - 0 = \nabla_\theta f(\theta)\)

So instead of using $Q(s,a)$ directly, we can use $Q(s,a) - V(s)$, where $V(s)$ is some baseline function.

The most natural choice for baseline is $V(s) =$ the expected reward from state $s$ (The value function). This represents “how good is this state on average?”

Our new gradient becomes: \(\nabla_\theta J(\theta) \approx \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} \sum_{t=1}^{T} \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_{i,t}|s_{i,t}) \cdot (Q(s_{i,t}, a_{i,t}) - V(s_{i,t}))\)

This is defined as the Advantage Function: \(A^{\pi}(s,a) = Q^{\pi}(s,a) - V^{\pi}(s)\)

The advantage function answers the question: “How much better is taking action $a$ in state $s$ compared to the average action in that state?”

- $A(s,a) > 0$: Action $a$ is better than average → increase its probability

- $A(s,a) < 0$: Action $a$ is worse than average → decrease its probability

- $A(s,a) = 0$: Action $a$ is exactly average → no change needed

Our final policy gradient becomes: \(\boxed{\nabla_\theta J(\theta) \approx \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} \sum_{t=1}^{T} \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_{i,t}|s_{i,t}) \cdot A^{\pi}(s_{i,t}, a_{i,t})}\)

Let’s understand why this reduces variance with an example:

Situation 1: Trajectory A gets +10 rewards, Trajectory B gets -10 rewards

- If average performance is 0: $A_A = +10$, $A_B = -10$

- Result: Increase A’s probability, decrease B’s probability ✓

Situation 2: Trajectory A gets +10 rewards, Trajectory B gets +1 rewards

- If average performance is +5.5: $A_A = +4.5$, $A_B = -4.5$

- Result: Increase A’s probability, decrease B’s probability ✓

Even when both trajectories have positive rewards, the advantage function correctly identifies which one is relatively better!

In deep learning, we want input features to be zero-centered. The advantage function does exactly this for our rewards:

- Without baseline: All positive rewards → always increase probabilities

- With advantage: Rewards centered around zero → increase good actions, decrease bad ones

This gives our policy gradient much clearer, less conflicting signals, significantly reducing variance and improving convergence.

Vanilla Policy Gradient Algorithm

Now that we understand the advantage function, let’s see how it all comes together in the complete algorithm:

\[\nabla U(\theta) \approx \hat{g} = \frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^{m} \nabla_\theta \log P(\tau^{(i)}; \theta)(R(\tau^{(i)}) - b)\](The notation may change from paper to paper, but the core idea remains the same)

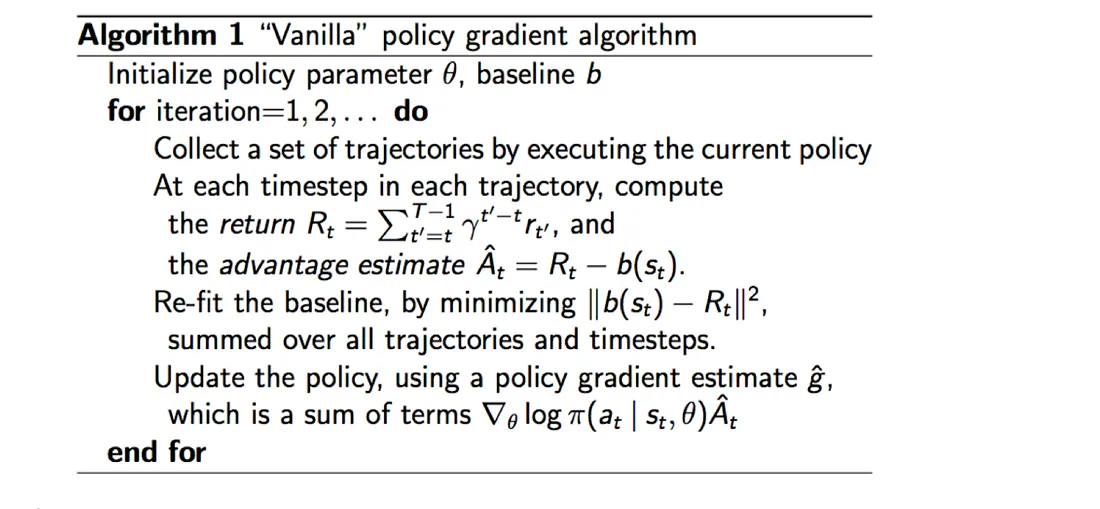

Image taken from RL — Policy Gradient Explained

Image taken from RL — Policy Gradient Explained

Reward Discount

There’s one more important technique that further reduces variance: reward discounting.

Reward discount reduces variance by reducing the impact of distant actions. The intuition is that actions taken now should have more influence on immediate rewards than on rewards received far in the future.

You can think of it in terms of money, would rather have money right now, or have it later.

Instead of using the raw cumulative reward, we use a discounted return:

\[Q^{\pi,\gamma}(s, a) \leftarrow r_0 + \gamma r_1 + \gamma^2 r_2 + \cdots | s_0 = s, a_0 = a\]Where:

- $\gamma \in [0,1]$ is the discount factor

- $\gamma = 0$: Only immediate rewards matter

- $\gamma = 1$: All future rewards are equally important

- $\gamma \approx 0.99$: Common choice that slightly prioritizes near-term rewards

The corresponding objective function becomes:

\[\nabla_\theta J(\theta) \approx \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} \sum_{t=1}^{T} \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_{i,t}|s_{i,t}) \left(\sum_{t'=t}^{T} \gamma^{t'-t} r(s_{i,t'}, a_{i,t'})\right)\]Why Discounting Helps:

- Reduces variance: Distant rewards have less influence, so random events far in the future don’t dominate the gradient

- Focuses learning: The agent learns to optimize for more predictable, near-term outcomes

- Mathematical stability: Prevents infinite returns in continuing tasks

All of this comprises the complete Vanila Policy Gradient Algorithm which serves as the foundation for more advanced methods like PPO, TRPO, and GRPO, which we’ll explore in subsequent sections.

TRPO

The Sample Efficiency Problem

Our vanilla policy gradient algorithm works, but it has a critical flaw that makes it impractical for real-world applications. Let’s examine what happens during training:

- Collect trajectories using current policy π_θ

- Compute gradients from these trajectories

- Update policy θ → θ_new

- Throw away all previous data and start over

This last step is the problem. Imagine training a robot to walk - every time you make a small adjustment to the policy, you must collect entirely new walking data and discard everything you learned before. For complex tasks requiring thousands of timesteps per trajectory, this becomes computationally prohibitive.

Recall our policy gradient formula:

\[\nabla_\theta J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim \pi_\theta}\left[\sum_{t=1}^{T} \nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t) \cdot A(s_t, a_t)\right]\]The expectation $\mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim \pi \theta}$ means we must sample trajectories using the current policy π_θ. When we update θ, this distribution changes, invalidating all our previous samples.

Importance Sampling

What if we could reuse old data to estimate the performance of our new policy? This is exactly what importance sampling enables. The core idea is beautifully simple:

| If you want to compute an expectation under distribution p, but you have samples from distribution q, you can reweight the samples by the ratio p/q. |

For any function f(x), the expectation under distribution p can be computed as:

\[\mathbb{E}_{x \sim p}[f(x)] = \sum_x p(x)f(x)\]But using importance sampling, we can compute this same expectation using samples from a different distribution q:

\[\mathbb{E}_{x \sim p}[f(x)] = \sum_x p(x)f(x) = \sum_x \frac{p(x)}{q(x)} \cdot q(x)f(x) = \mathbb{E}_{x \sim q}\left[\frac{p(x)}{q(x)} f(x)\right]\]The magic happens in that middle step - we multiply and divide by q(x), creating a ratio p(x)/q(x) that reweights our samples.

Let’s see this in action with an example. Suppose we want to compute the expected value of f(x) = x under two different distributions:

Distribution p: P(x=1) = 0.5, P(x=3) = 0.5

Distribution q: P(x=1) = 0.8, P(x=3) = 0.2

Direct calculation under p: \(\mathbb{E}_{x \sim p}[f(x)] = 0.5 \times 1 + 0.5 \times 3 = 2.0\)

Using importance sampling with samples from q:

If we sample from q and get samples [1, 1, 1, 3], we can estimate the expectation under p by reweighting:

For x=1: weight = p(1)/q(1) = 0.5/0.8 = 0.625

For x=3: weight = p(3)/q(3) = 0.5/0.2 = 2.5

The reweighted result matches our direct calculation!

Now we can revolutionize our policy gradient approach. Instead of:

\[\mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim \pi_\theta}[f(\tau)]\]We can use:

\[\mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim \pi_{\theta_{old}}}\left[\frac{\pi_\theta(\tau)}{\pi_{\theta_{old}}(\tau)} f(\tau)\right]\]Remember that trajectory probabilities factor as: \(\pi_\theta(\tau) = {p(s_1) \prod_{t=1}^{T} \pi_\theta(a_t|s_t)p(s_{t+1}|s_t, a_t)}\)

The environment dynamics $p(s_{t+1}|s_t, a_t)$ abd $p(s_1)$ are the same for both policies, so they cancel out in the ratio:

\[\frac{\pi_\theta(\tau)}{\pi_{\theta_{old}}(\tau)} = \frac{\prod_{t=1}^{T} \pi_\theta(a_t\|s_t)}{\prod_{t=1}^{T} \pi_{\theta_{old}}(a_t\|s_t)} = \prod_{t=1}^{T} \frac{\pi_\theta(a_t|s_t)}{\pi_{\theta_{old}}(a_t|s_t)}\]Our objective becomes:

\[J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim \pi_{\theta_{old}}}\left[\prod_{t=1}^{T} \frac{\pi_\theta(a_t|s_t)}{\pi_{\theta_{old}}(a_t|s_t)} \cdot R(\tau)\right]\]This is huge! We can now:

- Collect data with policy ${\pi_{\theta_{old}}}$

- Reuse this data multiple times to evaluate different policies ${\pi_{\theta}}$

- Dramatically improve sample efficiency

But there’s a catch. Importance sampling works well only when the two distributions are similar. If πθ becomes very different from πθ_old, the probability ratios can explode or vanish:

- Ratio » 1: New policy assigns much higher probability to some actions

- Ratio « 1: New policy assigns much lower probability to some actions

- Ratio ≈ 0: Catastrophic - new policy never takes actions the old policy preferred

Consider what happens if one action has ratio = 100 while others have ratio = 0.01. A single high-ratio sample can dominate the entire gradient estimate, leading to:

- Unstable training: Gradients vary wildly between batches

- Poor convergence: The algorithm makes erratic updates

- Sample inefficiency: We need many more samples to get reliable estimates

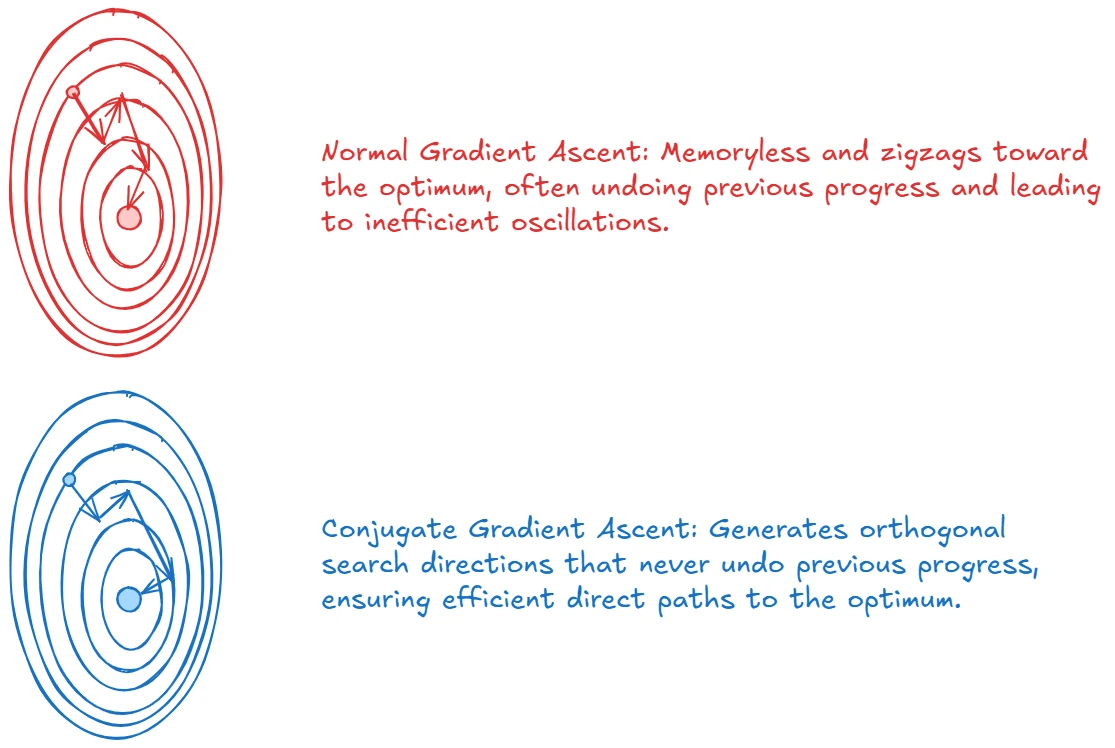

Constrained Policy Updates

The breakthrough insight: constrain how much the policy can change to keep importance sampling ratios well-behaved. This leads us naturally to the concept of trust regions - regions where we trust our importance sampling approximation to be accurate.

But, we must also ask. How do we guarantee that our policy updates always improve performance?

These observations bring us to two key concepts:

- The Minorize-Maximization (MM) algorithm

- Trust regions

Minorize-Maximization (MM) Algorithm

Can we guarantee that any policy update always improves the expected rewards? This seems impossible, but it’s theoretically achievable through the MM algorithm.

The idea: Instead of directly optimizing the complex true objective η(θ), we iteratively optimize simpler lower bound functions M(θ) that approximate η(θ) locally.

The MM algorithm follows this iterative process:

- Find a lower bound M that approximates the expected reward η locally at the current guess θ_i

- Optimize the lower bound M to find the next policy guess θ_{i+1}

- Repeat until convergence

For this to work, M must be:

- A lower bound: M(θ) ≤ η(θ) for all θ

- Tight at current point: M(θ_i) = η(θ_i)

- Easier to optimize: M should be simpler than η (typically quadratic)

The lower bound function has the form: $M(\theta) = g \cdot (\theta - \theta_{old}) - \frac{1}{2}(\theta - \theta_{old})^T F (\theta - \theta_{old})$

This is a quadratic approximation where:

- g is the gradient at θ_old

- F is a positive definite matrix (often related to the Hessian)

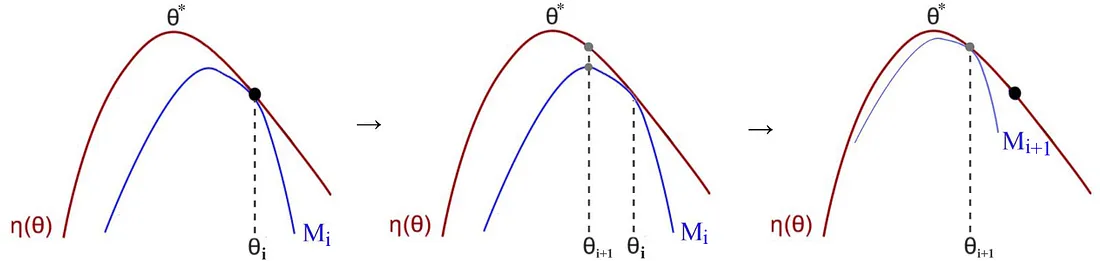

Image taken from RL — Trust Region Policy Optimization (TRPO) Explained

Image taken from RL — Trust Region Policy Optimization (TRPO) Explained

If M is a lower bound that never crosses η, then maximizing M must improve η.

Proof sketch:

- Since $M(\theta_{\text{old}}) = \eta(\theta_{\text{old}})$ and $M(\theta) \leq \eta(\theta)$ everywhere

- If we find $\theta_{\text{new}}$ such that $M(\theta_{\text{new}}) > M(\theta_{\text{old}})$

- Then $\eta(\theta_{\text{new}}) \geq M(\theta_{\text{new}}) > M(\theta_{\text{old}}) = \eta(\theta_{\text{old}})$

- Therefore $\eta(\theta_{\text{new}}) > \eta(\theta_{\text{old}})$ ✓

In simpler terms, we have a function $\eta(\theta)$ parameterized by $\theta$ (the weights of our neural network). It is not computationally tractable to optimize this function directly. Hence we create a close approximation function $M(\theta)$ using the lower bound function form described above. This approximation comes from the general theory of Minorize-Maximization algorithms (see Hunter & Lange, 2004).

This approximation $M(\theta)$ is computationally feasible and easier to optimize. What we have proved here is that as we improve $M(\theta)$, that improvement guarantees we also improve $\eta(\theta)$.

| By optimizing a lower bound function approximating η locally, MM guarantees policy improvement every iteration and leads us to the optimal policy eventually. |

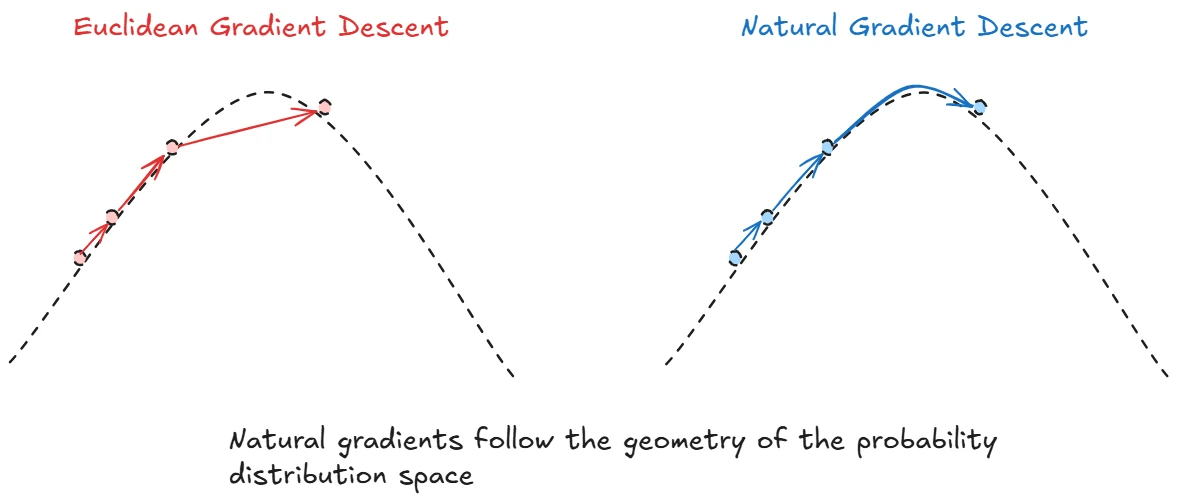

Trust Regions

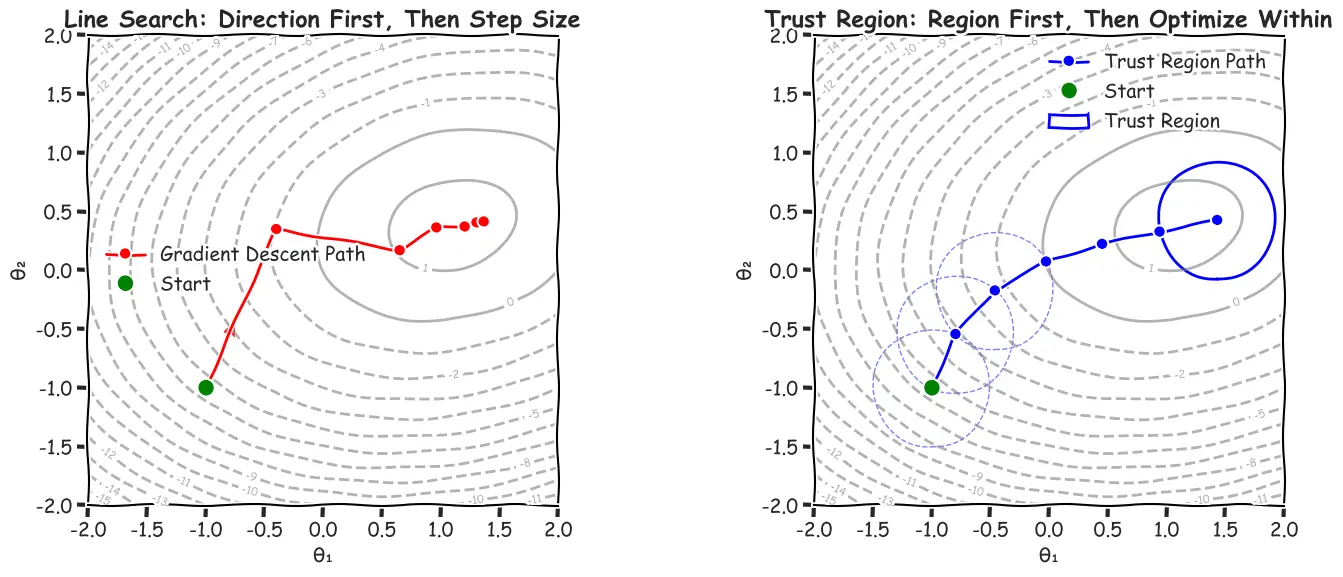

There are two major optimization paradigms:

- Line Search (like gradient descent): Choose direction first, then step size

- Trust Region: Choose maximum step size first (the size of the trust region), then find optimal point within that region

In trust region methods, we:

- Define a trust region of radius δ around current policy θ_old

- Find the optimal policy within this constrained region

- Adapt the radius based on how well our approximation worked

The optimization problem becomes: $\max_{\theta} \; M(\theta)$ $\text{subject to} \; |\theta - \theta_{old}| \leq \delta$

Adaptive Trust Region Sizing

The trust region radius δ can be dynamically adjusted:

- If approximation is good: Expand δ for next iteration

- If approximation is poor: Shrink δ for next iteration

- If policy diverges too much: Shrink δ to prevent importance sampling breakdown

Why Trust Regions Work for RL

In reinforcement learning, trust regions serve a dual purpose:

- Mathematical: Keep our quadratic approximation M valid

- Statistical: Prevent importance sampling ratios from exploding

When policies change too much, both our lower bound approximation AND our importance sampling become unreliable. Trust regions keep us in the safe zone for both.

Mathematical Notation Reference

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| $\pi_\theta(a|s)$ | Policy probability of action a given state s |

| $\pi_{\theta_{old}}(a|s)$ | Old policy probability |

| $\tau$ | Trajectory $(s_1, a_1, s_2, a_2, \ldots)$ |

| $\pi_\theta(\tau)$ | Probability of trajectory under policy $\pi_\theta$ |

| $\frac{\pi_\theta(a_t|s_t)}{\pi_{\theta_{old}}(a_t|s_t)}$ | Importance sampling ratio for single timestep |

| $\prod_{t=1}^{T} \frac{\pi_\theta(a_t|s_t)}{\pi_{\theta_{old}}(a_t|s_t)}$ | Importance sampling ratio for full trajectory |

| $R(\tau)$ | Total reward of trajectory |

| $A(s_t, a_t)$ | Advantage function |

| $\eta(\theta)$ | Expected reward under policy $\pi_\theta$ |

| $M(\theta)$ | Lower bound function in MM algorithm |

| $\theta_{old}$ | Current policy parameters |

| $\delta$ | Trust region radius |

| $F$ | Positive definite matrix (approximating curvature) |

| $g$ | Policy gradient vector |

Trust Region Policy Optimization (TRPO)

Now we can finally understand how TRPO elegantly combines all the concepts we’ve explored:

- Importance Sampling - to reuse old data efficiently

- MM Algorithm - to guarantee policy improvement

- Trust Regions - to constrain policy changes and keep approximations valid

TRPO is a culmination of these ideas into a practical, theoretically-grounded algorithm.

Recall that our original objective was:

\[J(\pi) = \mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim \pi}[R(\tau)]\]This is the expected return (total reward) when following policy π. Instead of maximizing absolute performance $J(\pi’)$, TRPO maximizes the policy improvement:

\[\max_{\pi'} J(\pi') - J(\pi)\]This is mathematically equivalent to maximizing $J(\pi’)$ (since $J(\pi)$ is constant), but conceptually important - we’re explicitly measuring progress from our current policy.

Why focus on improvement? Because we can construct better approximations for the improvement $J(\pi’) - J(\pi)$ than for the absolute performance $J(\pi’)$. The MM algorithm works by finding lower bounds for this improvement.

To apply the MM algorithm, TRPO constructs a lower bound function ℒ that uses importance sampling:

\[\mathcal{L}_\pi(\pi') = \frac{1}{1-\gamma} \mathbb{E}_{s\sim d^\pi} \left[ \frac{\pi'(a|s)}{\pi(a|s)} A^\pi(s,a) \right] = \mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim \pi} \left[ \sum_{t=0}^{\infty} \gamma^t \frac{\pi'(a_t|s_t)}{\pi(a_t|s_t)} A^\pi(s_t, a_t) \right]\]ℒ looks complex, but let’s break this down piece by piece to understand what’s really happening here.

The discounted state visitation distribution $d^\pi(s)$ tells us how often we expect to visit each state when following policy π:

\[d^\pi(s) = (1-\gamma) \sum_{t=0}^{\infty} \gamma^t P(s_t = s|\pi)\]Think of this as a “popularity contest” for states. If γ = 1, this becomes just the regular state visit frequency under policy π. But when γ < 1, we care more about states we visit early in episodes than those we reach later. It’s like asking: “If I run my policy many times, which states will I spend most of my time in, giving more weight to earlier visits?”

The advantage function $A^\pi(s,a)$ we’ve already met - it tells us how much better taking action $a$ in state $s$ is compared to what the policy would do on average in that state.

But here’s where the magic happens. The function ℒ is essentially asking a clever question using importance sampling: “If I reweight all the actions my current policy π took according to how likely my new policy π’ would be to take them, what would my expected advantage be?”

This is brilliant because it lets us estimate how well policy π’ would perform without actually running it in the environment. We just take all our old experience from policy π and reweight it according to the probability ratio $\frac{\pi’(a|s)}{\pi(a|s)}$. When the new policy is more likely to take an action than the old one, we give that experience more weight. When it’s less likely, we give it less weight.

This importance sampling approach is what allows TRPO to reuse old data efficiently - a huge computational win over vanilla policy gradients that throw away all previous experience after each update.

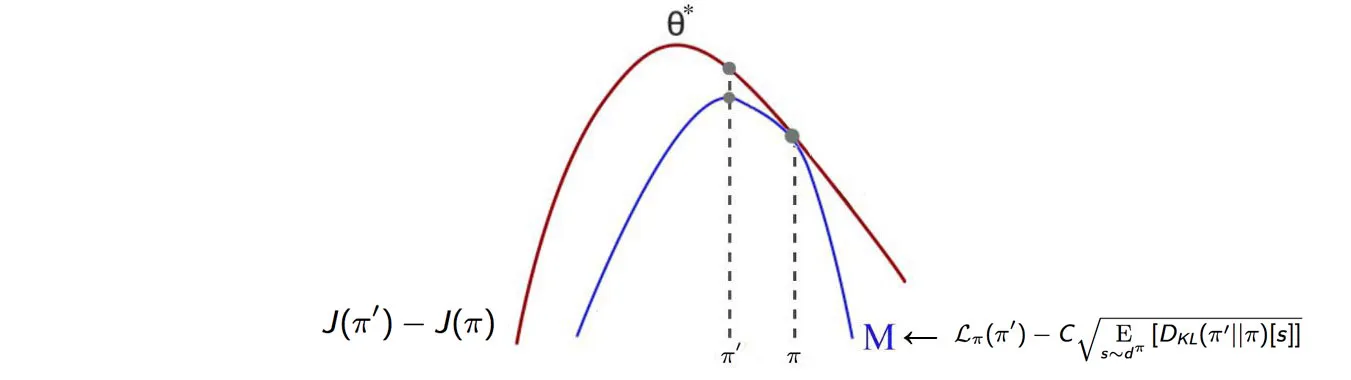

The theoretical foundation comes from this crucial bound (proven in Appendix 2 of the TRPO paper):

\[J(\pi') - J(\pi) \geq \mathcal{L}_\pi(\pi') - C\sqrt{\mathbb{E}_{s\sim d^\pi}[D_{KL}(\pi' \| \pi)[s]]}\]This tells us:

- Left side: True policy improvement

- Right side: Our lower bound estimate minus a penalty term

The penalty term grows with KL divergence, so the bound becomes loose when policies differ too much.

| Consider reading this blog to get a better idea about KLD |

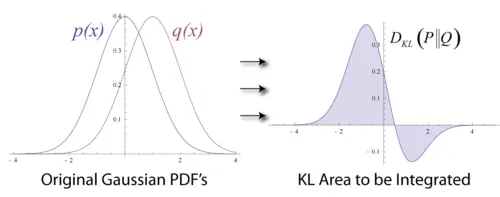

Image taken from Wikipedia

Image taken from Wikipedia

The KL divergence measures how different two probability distributions are:

\[D_{KL}(P \| Q) = \sum_x P(x) \log \frac{P(x)}{Q(x)}\]For continuous distributions, this becomes:

\[D_{KL}(P \| Q) = \int P(x) \log \frac{P(x)}{Q(x)} dx\]Think of KL divergence as asking: “If I have samples from distribution P, how surprised would I be if I thought they came from distribution Q instead?” When the distributions are identical, KL divergence is zero. As they become more different, the divergence grows.

TRPO can be formulated in two mathematically equivalent ways:

KL-Penalized (Unconstrained): \(\max_{\pi'} \mathcal{L}_\pi(\pi') - C\sqrt{\mathbb{E}_{s\sim d^\pi}[D_{KL}(\pi' \| \pi)[s]]}\)

KL-Constrained: \(\max_{\pi'} \mathcal{L}_\pi(\pi')\) \(\text{subject to } \mathbb{E}_{s\sim d^\pi}[D_{KL}(\pi'||\pi)[s]] \leq \delta\)

These formulations arise directly from the theoretical bound we mentioned earlier:

\[J(\pi') - J(\pi) \geq \mathcal{L}_\pi(\pi') - C\sqrt{\mathbb{E}_{s\sim d^\pi}[D_{KL}(\pi'||\pi)[s]]}\]The unconstrained version simply maximizes this lower bound directly. The constrained version takes a different approach: instead of penalizing large KL divergences, it prevents them entirely by adding a hard constraint.

These are mathematically equivalent due to Lagrangian duality - a beautiful result from optimization theory. For every penalty coefficient C in the unconstrained problem, there exists a constraint threshold δ in the constrained problem that gives the same optimal solution. You can think of it like this: instead of saying “I’ll pay a penalty for going over the speed limit,” you’re saying “I absolutely won’t go over the speed limit.” Both approaches can lead to the same driving behavior, just with different enforcement mechanisms.

The lower bound is what we try to maximize to find the optimum $\theta$

Image taken from here

Image taken from here

However, in practice, the constrained formulation wins by a landslide. Here’s why: the penalty coefficient C becomes a nightmare to tune when the discount factor γ gets close to 1. As γ approaches 1, the coefficient explodes, making the algorithm incredibly sensitive to small changes in γ. Imagine trying to tune a parameter that changes by orders of magnitude when you adjust γ from 0.99 to 0.995 - it’s practically impossible.

\[C \propto 1/(1-\gamma)^2\]The constrained version, on the other hand, gives you direct, interpretable control. The parameter δ simply says “don’t let the policy change too much,” which is much easier to understand and tune across different environments. It’s the difference between having a thermostat that directly controls temperature versus one that requires you to calculate complex equations involving heat transfer coefficients.

| This practical insight would later inspire PPO’s breakthrough innovation. PPO took the unconstrained formulation and made it work brilliantly by replacing the complex second-order penalty with a simple first-order clipping mechanism. Instead of computing expensive Fisher Information Matrices, PPO just clips the importance sampling ratios directly - achieving similar performance with a fraction of the computational cost. |

The beauty of TRPO lies in its theoretical guarantee. Since we have the fundamental bound:

\[J(\pi') - J(\pi) \geq \mathcal{L}_\pi(\pi') - C\sqrt{\mathbb{E}_{s\sim d^\pi}[D_{KL}(\pi'(·|s) \| \pi(·|s))]}\]TRPO’s algorithm ensures three key things happen:

- Optimize $\mathcal{L}_\pi(\pi’)$ using importance sampling

- Constrain the KL divergence to stay small

- Rely on the fact that $\mathcal{L}_\pi(\pi) = 0$ when $\pi’ = \pi$

This last point is crucial and deserves explanation.

Why is ℒ_π(π) = 0? At the current policy, the importance sampling ratio becomes $\frac{\pi(a|s)}{\pi(a|s)} = 1$ for all actions. So we get:

\[\mathcal{L}_\pi(\pi) = \mathbb{E}_{s\sim d^\pi} \left[ \mathbb{E}_{a \sim \pi} \left[ 1 \cdot A^\pi(s,a) \right] \right] = \mathbb{E}_{s\sim d^\pi} \left[ \mathbb{E}_{a \sim \pi} \left[ A^\pi(s,a) \right] \right]\]But by definition, the advantage function has zero expectation under the policy - $\mathbb{E}_{a \sim \pi}[A^\pi(s,a)] = 0$ because it measures how much better each action is compared to the average. This means if we can make ℒ_π(π’) > 0 while keeping KL divergence small, we’re guaranteed that J(π’) > J(π). TRPO never moves backwards.